Stop and Frisk

Hi Friends!

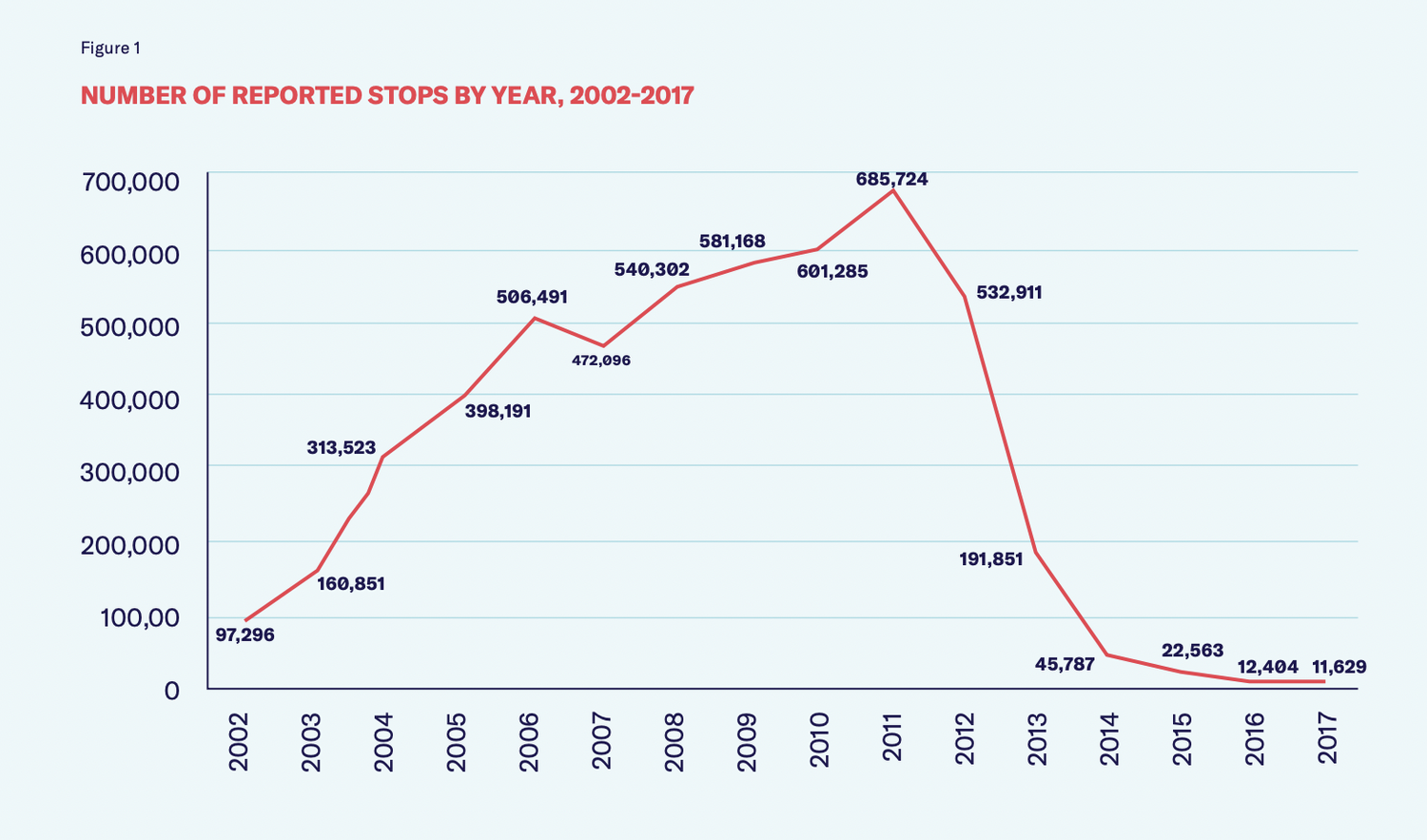

Welcome to Issue 53 of this newsletter. This week’s topic is: Stop and Frisk. I was inspired to write on this topic from some of my reading for a class I’m taking at Columbia called “Human Rights in the United States”. Stop and frisk was up for debate at the 1968 Terry v. Ohio supreme court case which found it to be legal, and set this precedent: “Under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may stop a suspect on the street and frisk him or her without probable cause to arrest, if the police officer has a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime and has a reasonable belief that the person ‘may be armed and presently dangerous.’" Outside of New York, this practice is known as a Terry Stop, based on the name of the case. However, in 2013, in Floyd v. City of New York, US District Court Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that stop-and-frisk had been used in an unconstitutional manner due to racial profiling and directed the police to adopt a written policy to specify where such stops are authorized. Stop and frisk was a signature policy of the Bloomberg administration beginning in 2002 and reaching its peak in 2011 with over 600,000 incidents that year alone. A . According to a highly researched study by the NYCLU, “over 97 percent of all stops that occurred from 2003-2021 took place during [Bloomberg’s] time in office.” Stop and frisk never reduced crime, but always took a toll of Black and Latinx communities. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Stop and frisk: The controversial policy allowed police officers to stop, interrogate and search New York City citizens on the sole basis of “reasonable suspicion.”

Terry v. Ohio: A Cleveland detective (McFadden), on a downtown beat which he had been patrolling for many years, observed two strangers (petitioner and another man, Chilton) on a street corner. Suspecting the two men of "casing a job, a stick-up," the officer followed them and saw them rejoin the third man a couple of blocks away in front of a store. The officer approached the three, identified himself as a policeman, spun petitioner around, patted down his outside clothing, and found in his overcoat pocket, but was unable to remove, a pistol. . The court distinguished between an investigatory "stop" and an arrest, and between a "frisk" of the outer clothing for weapons and a full-blown search for evidence of crime. Under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may stop a suspect on the street and frisk him or her without probable cause to arrest, if the police officer has a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime and has a reasonable belief that the person "may be armed and presently dangerous."

Floyd v. City of New York: The Center for Constitutional Rights filed the federal class action lawsuit Floyd, et al. v. City of New York, et al. against the City of New York to challenge the New York Police Department’s practices of racial profiling and unconstitutional stop and frisks of New York City residents. The named plaintiffs in the case – David Floyd, David Ourlicht, Lalit Clarkson, and Deon Dennis – represent the thousands of primarily Black and Latino New Yorkers who have been stopped without any cause on the way to work or home from school, in front of their house, or just walking down the street. In a historic ruling on August 12, 2013, following a nine-week trial, a federal judge found the New York City Police Department liable for a pattern and practice of racial profiling and unconstitutional stops. Floyd focuses not only on the lack of any reasonable suspicion to make these stops, in violation of the Fourth Amendment, but also on the obvious racial disparities in who is stopped and searched by the NYPD.

Broken Windows Theory: Kelling and Wilson suggested that a broken window or other visible signs of disorder or decay — think loitering, graffiti, prostitution or drug use — can send the signal that a neighborhood is uncared for. So, they thought, if police departments addressed those problems, maybe the bigger crimes wouldn't happen. Stop and frisk was seen as a way of managing this. Kelling and Wilson proposed that police departments change their focus. Instead of channeling most resources into solving major crimes, they should instead try to clean up the streets and maintain order — such as keeping people from smoking pot in public and cracking down on subway fare beaters. If broken windows meant arresting people for misdemeanors in hopes of preventing more serious crimes, "stop and frisk" said, why even wait for the misdemeanor? Why not go ahead and stop, question and search anyone who looked suspicious? In Chicago, the researchers Robert Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush analyzed what makes people perceive social disorder. They found that if two neighborhoods had exactly the same amount of graffiti and litter and loitering, people saw more disorder, more broken windows, in neighborhoods with more African-Americans.

Let’s Get Into It

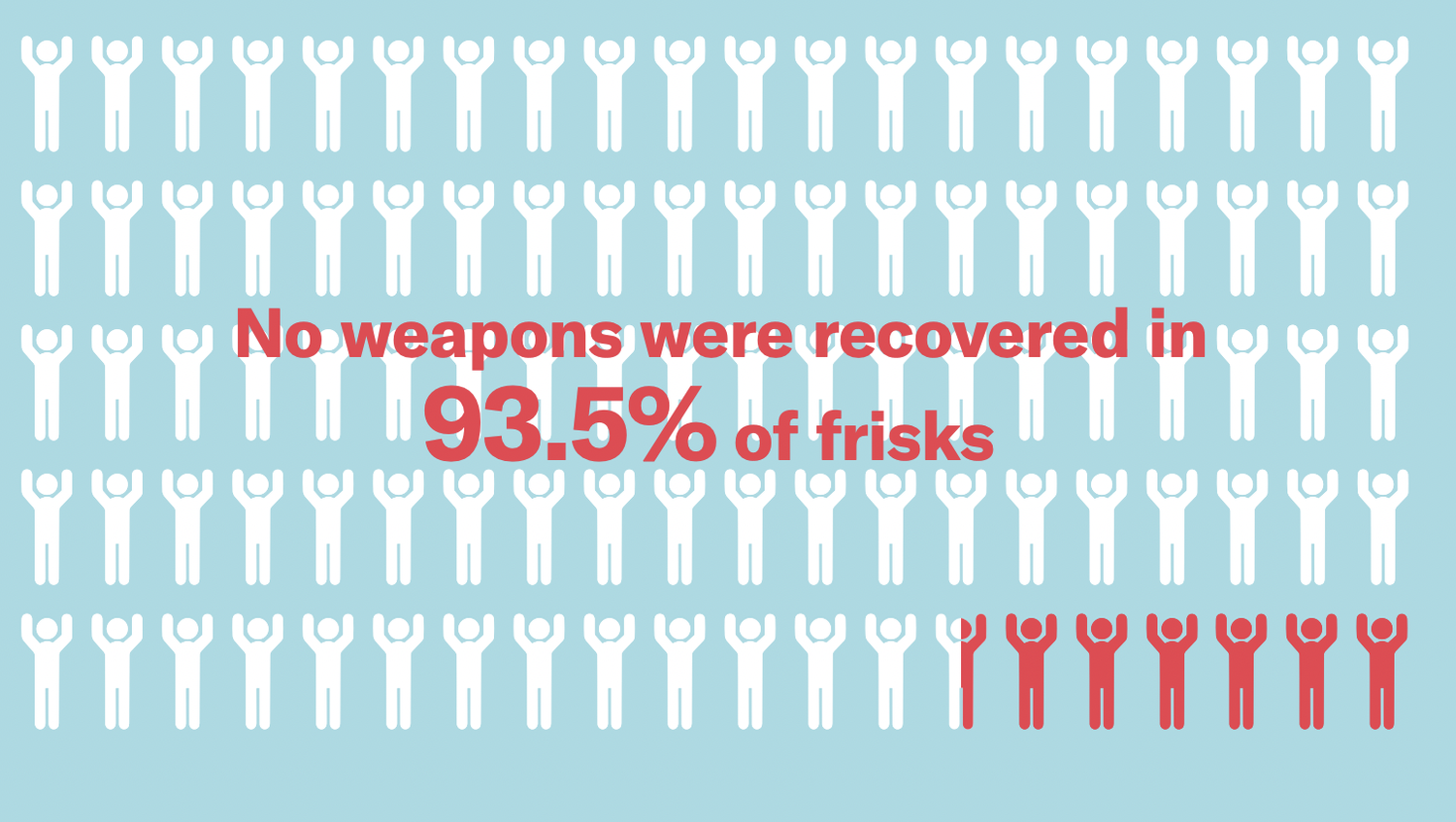

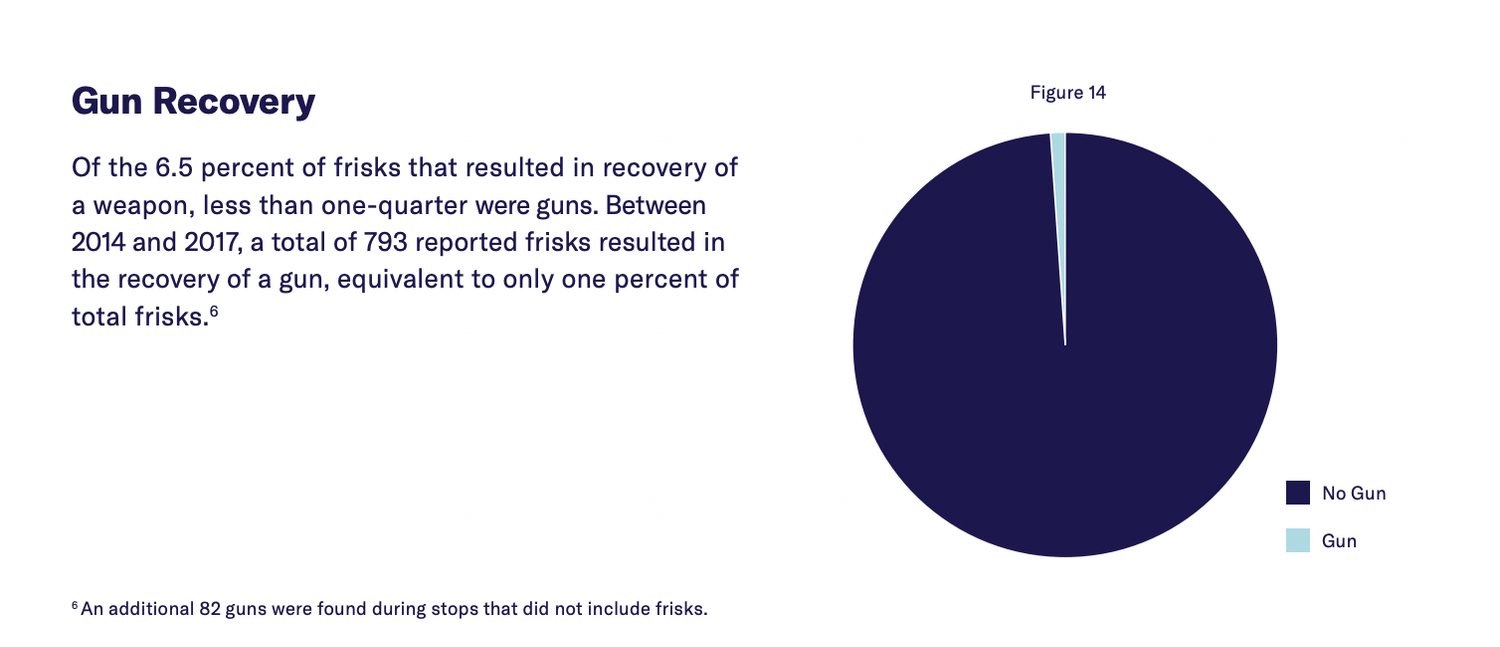

A 2019 report by NYCLU on Stop and Frisk encapsulated so much relevant information to how this system has operated in New York City, so all of the info below will be pulled from there.

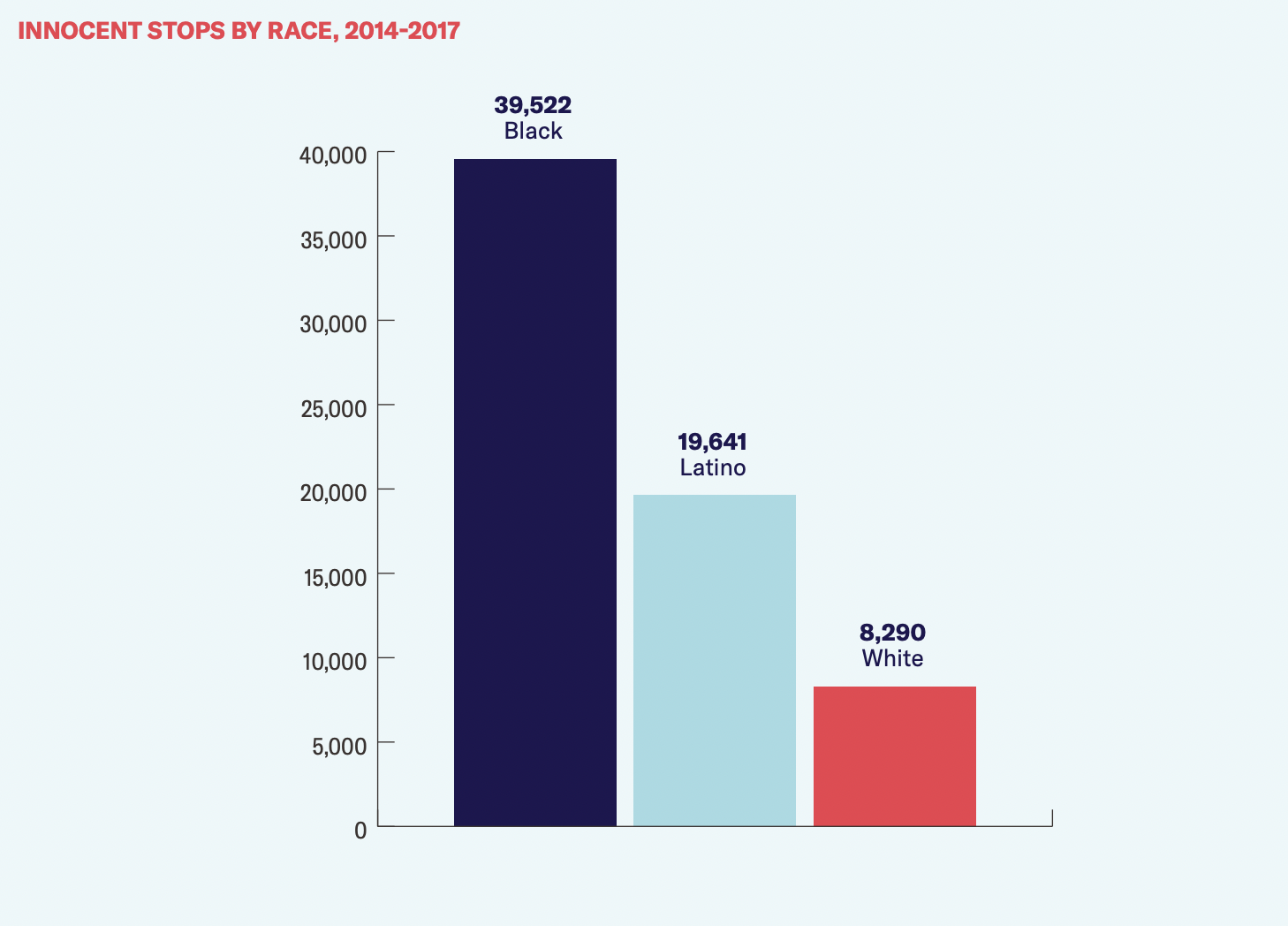

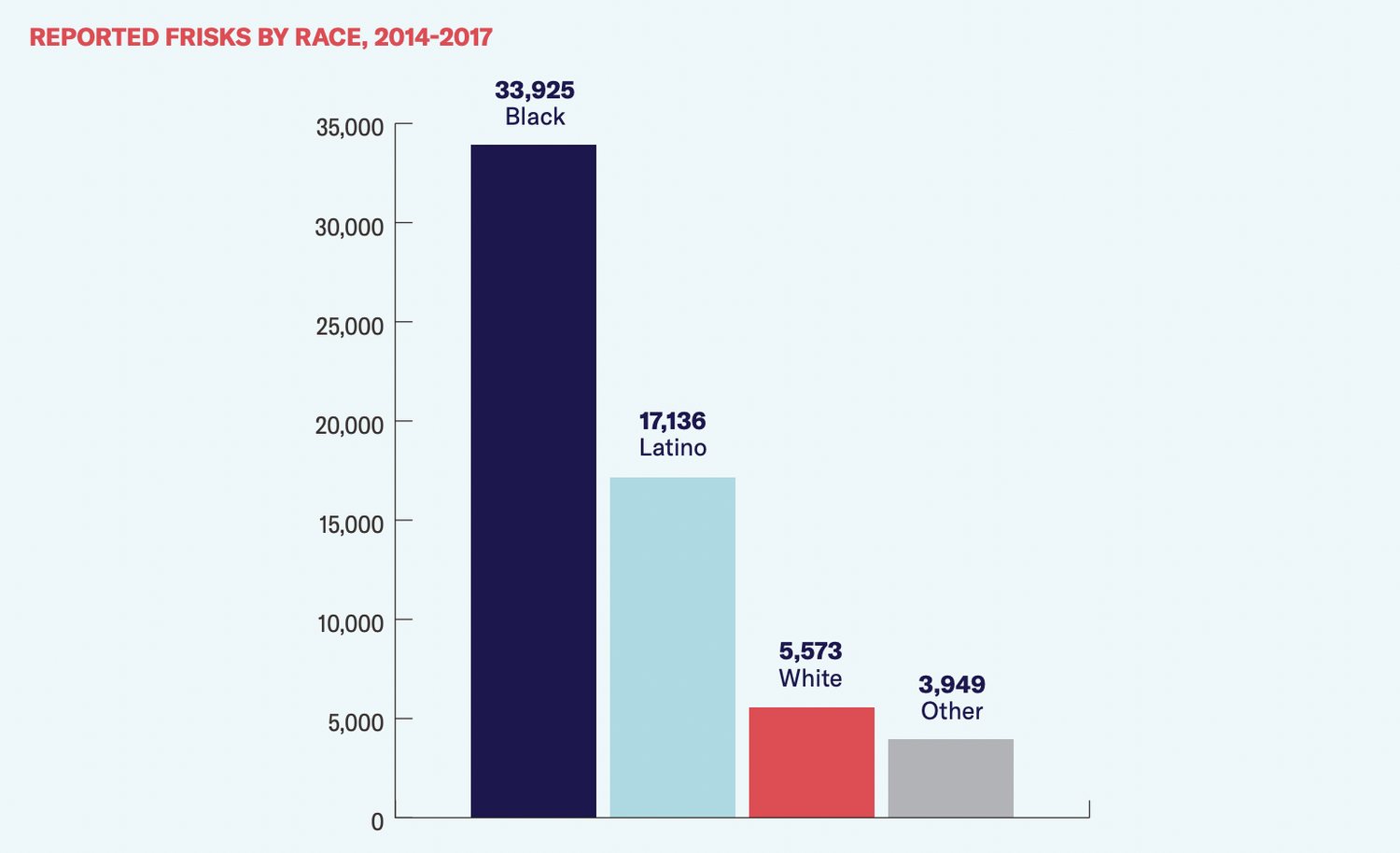

The New York City Police Department’s aggressive stop-and-frisk program exploded into a national controversy during the mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg, as the number of NYPD stops each year grew to hundreds of thousands. Most of the people stopped were black and Latino, and nearly all were innocent. Stop-and-frisk peaked in 2011, when NYPD officers made nearly 700,000 stops.

It is notable that “actions of engaging in a violent crime” was a reason listed in only seven percent of reported stops between 2014 and 2016. During the height of stop-and-frisk, the NYPD routinely argued that the disproportionate number of stops of Black people was justified because, according to the department, Black people are disproportionately involved in violent crimes. Given that over 90 percent of stops had nothing to do with a suspected violent crime, the race of those convicted of violent crimes generally cannot explain the disproportionate number of Black people stopped every year

Stops of Males Age 14-24

24.9% (22,998) Young Black Males but only 1.9% (158,406) of NYC’s population

12.8% (11,193) Young Latino Males but only 2.8% (226,677) of NYC’s population

In 2011, 685,724 NYPD stops were recorded — this is at the peak of Stop and Frisk under Bloomberg

605,328 were innocent (88 percent).

350,743 were Black (53 percent).

223,740 were Latinx (34 percent).

61,805 were white (9 percent).

In 2021, 8,947 stops were recorded.

5,422 were innocent (61 percent).

5,404 were Black (60 percent).

2,457 were Latinx (27 percent).

732 were white (8 percent).

192 were Asian / Pacific Islander (2 percent)

71 were Middle Eastern/Southwest Asian (1 percent)