Weekly Anti-racism NewsletteR

Because it ain’t a trend, honey.

-

Taylor started her newsletter in 2020 and has been the sole author of almost one hundred blog mosts and almost two hundred weekly emails. A lifelong lover of learning, Taylor began researching topics of interest around anti-racism education and in a personal effort to learn more about all marginalized groups. When friends asked her to share her learnings, she started sending brief email synopsises with links to her favorite resources or summarizing her thoughts on social media. As the demand grew, she made a formal platform to gather all of her thoughts and share them with her community. After accumulating thousands of subscribers and writing across almost one hundred topics, Taylor pivoted from weekly newsletters to starting a podcast entitled On the Outside. Follow along with the podcast to learn more.

-

This newsletter covers topics from prison reform to colorism to supporting the LGBTQ+ community. Originally, this was solely a newsletter focused on anti-racism education, but soon, Taylor felt profoundly obligated to learn and share about all marginalized communities. Taylor seeks guidance from those personally affected by many of the topics she writes about, while always acknowledging the ways in which her own privilege shows up.

Affirmative Action: Part 2

Today, we’ll discuss the impact and implications of affirmative action and the most recent Supreme Court decision. Personally, I benefited from affirmative action as an undergrad at NYU. As a Black, Hispanic, first-generation women, I am part of several underrepresented and marginalized communities.

Hi Friends,

Welcome to Issue 57 of this newsletter. This week’s topic is: Affirmative Action, following up after our first newsletter on the topic. If you haven’t read that newsletter yet, I highly recommend it. In that newsletter we discussed the history and background of affirmative action. Today, we’ll discuss the impact and implications of affirmative action and the most recent Supreme Court decision. Personally, I benefited from affirmative action as an undergrad at NYU. As a Black, Hispanic, first-generation women, I am part of several underrepresented and marginalized communities. Socio-economically, I grew up understanding I would need a scholarship to be able to pursue higher education. My high school was ranked among the bottom 50% of public schools in New Jersey with only 43% of students achieving reading proficiency. As an adult, I am blown away when my peers talk about internships, fellowships, summer programs and organizations that they participated in while in high school because I never had the opportunity to participate in any of them. I thought being drama club president and on every single club (multicultural club, key club, national honor society) meant that I was doing the absolute maximum in school participation. The issue was — I didn’t know what I didn’t know. I did not understand that there were so many opportunities I was missing out on because I had never heard of them. Because of the systemic disadvantage that I faced having immigrant parents and attending a low ranking public school, I am so grateful that NYU took a holistic approach to my application, understanding the levels of disadvantages I had while also appreciating the ways in which I succeeded with the opportunities I was given. I had a great essay. I scored a perfect score on the language and writing sections of the SATs. I was in the top 5% of my graduating class. I took and passed 4 AP exams. I was the National Honor Society vice president. I worked hard. I just didn’t see all of the ways that my particular corner of the world lacked the access to a lot of things that could have made me even better. This is a conversation close to my heart. Let’s get into it.

Lets Get Into It

Successes of Affirmative Action

Affirmative action reduces discrimination in education and employment settings

Students who benefit from affirmative action are more likely to graduate college and to earn professional degrees, and have higher incomes. So affirmative action acts as an engine for social mobility for its direct beneficiaries. This in turn leads to a more diverse leadership, which you can see steadily growing in the United States

Affirmative action has helped increase the percentage of Black Americans in medical school by a factor of four

Affirmative action can improve police-community relations. Police departments throughout many states used affirmative action planning to determine any problem areas with respect to minority representation among their workforce. Subsequently, those departments have increased their complement of officers from racial minority groups. A study of the fifty largest cities in the United States had shown that from 1983 to 1992, police departments, using AAP, “made progress in the employment of African-American and Hispanic officers.”

Affirmative action forbids employers to discriminate against individuals because of their race, color, religion, sex, or national origin

The Supreme Court Ruling

Ultimately, the most recent Supreme Court ruling was against the use of affirmative action — saying in the majority opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts that the systems in place "lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points, those admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause.” But the court did not rule out race entirely in admission programs, adding, "nothing prohibits universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected the applicant’s life, so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character or unique ability that the particular applicant can contribute to the university."

Some important points to note are:

While the ruling focuses specifically on barring race as a factor in admissions, it doesn't limit institutions' outreach, engagement, retention or completion strategies aimed at enrolling diverse student bodies. Higher education scholars and counselors say the onus is on colleges and universities to ensure that their applicant pools include students of color — many of whom come from segregated school districts with fewer resources (like me!)

Higher education institutions will be able to continue to “promote diversity based on background, based on socioeconomic experiences,” among other experiences. A wide array of experiences can still define what it means to have a diverse student body — including students' experiences, where they grew up and their areas of interest.

Banning affirmative action on a state-level is not new. It is staggering, however, to be experiencing this on a national level. State-level bans on using race-based affirmative action in Arizona, California, Florida, Idaho, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma and Washington have already given the country a glimpse of the consequences of prohibiting such a practice. Research shows that in those nine states, the enrollment of students from underrepresented communities declined, even if other factors, such as class, were weighed more heavily.

What's important to note, experts say, is that race was just one factor used to determine admissions at some selective colleges and universities — along with students' academic records, extracurricular activities, essays, recommendations and standardized test scores for some schools. No university has ever used race alone to admit a student.

The new ruling says a college or university can’t use race as a factor in determining whether a student should be admitted. But students can still convey their racial or ethnic backgrounds through extracurricular activities and other application materials, such as essays and personal statements. HOWEVER, it’s possible that some colleges and universities may, on their own, in response to the Supreme Court decision, forbid candidates from using their race so it can be said that they’re making their decisions without regard to race.

Here’s what the Supreme Court opinion stated: “Nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise."That essentially means that if students talk about their race or ethnic backgrounds in their essays or mission statements, "then the university can consider it, to the extent of the relevance," Ben-Dan said. However, "the court gave no guidance whatsoever as to how this consideration is supposed to happen."

Some negative repercussions to this decision may be:

This ruling minimizes the significant achievement of marginalized students by suggesting they’ve been given unfair advantages

The racial gap in higher education may get worse without institutions making an effort to diversify their application pool. In many states, Black students make up between 20% to 50% of public high school graduates. In those same states only 5% or 8% of freshman are Black at those same states flagship schools. 49% of Mississippi’s public school graduates in 2020 were Black and only 8% of freshman at the University of Mississippi were Black. For Latino students who make up between 20% and over 50% of public high school graduates, only 9% to 30% of freshman are Latino in those state’s flagship schools. In California, 53% of students who graduated in 2020 were Latino and only 22% of the freshman class at University of California-Berkeley were Latino.

Underrepresented students may choose not to apply to higher education in the wake of affirmative action programs being deemed unconstitutional. This decision tells students of color that their idenities and the ways in which their race impacts their experiences does not matter. It does matter. Color-blindness is not the goal of equality. Equality is contingent on being seen for and respected because of who we are as individuals, as Americans, as human beings, in a world that is tarnished by racism, chattle slavery, implicit bias and inequality. Against that background, it’s important to pay special attention to first-generation students, as well as to those who identify as Black or Latino, because they are more likely to “self-select out of going to a selective school,” said Eva Garza-Nyer, a counselor and the CEO of Texas College Advisor. “They’ll just assume ‘I have no chance.’”

Legacy Preference & Historical Disadvantages

Legacy preference means that a candidate whose family members attended the same college gets preferential treatment for their application. The history of legacy preference is explicitly racist and anti semitic. According to the ACLU, it is estimated that legacy applicants are five times as likely to be admitted to Harvard as other applicants — why is this allowed, but affirmative action is not?

Legacy admissions reinforce privilege. Harvard was founded in 1636 and was the first institution of higher education in the English colonies. In 1835, Oberlin College in Ohio became the first American college to accept Black students, men, and women. In 1869, Mary Ann Shadd Carey became the first Black woman to enroll at Howard University's Law Department.

This means that a white person today could have family legacy dating back 387 years at Harvard compared to a Black person today who could have family legacy dating back 188 years to Oberlin and no more than 154 years at Harvard. A white American could have family attending an American university for more than double the length that a Black American ever could.

Legacy preference in and of itself reduces opportunities for students from underrepresented or disadvantaged backgrounds by prioritizing applicants with family connections. This perpetuates the lack of diversity in educational institutions and may hinder efforts to create a more inclusive learning environment.

Legacy preferences can impede social mobility by making it harder for talented and motivated students from lower-income families to access top-tier institutions. This contributes to the cycle of inequality, where wealth and privilege remain concentrated among certain groups.

Let’s be clear, white teens applying to universities and colleges who have parents and grandparents that have also attended those institutions have been multiple layers of privilege and advantage over students from underrepresented and marginalized groups. Let’s name a few. First of all, that applicant is more than likely to come from a wealthier household. According to 2021 Bureau of Labor Statistics data, someone with a college degree will earn $524 more per week, $27,000 more per year, and $1 million more over a lifetime than someone with only a high school diploma or less. If one or both parents have a college degree and one or both sets of grandparents have a college degree, the family has significant opportunities to accumulate generational wealth. Having money means a lot. They might have been able to accept unpaid internships, mentorships and participated in more after-school activities because they did not have to work. Having parents in a professional industry might open doors for them to work at their family business, make connections with family friends in other industries and grain firsthand experience about their parents career path. They will also enter into higher education with knowledge from their parents on how to navigate school, what organizations to belong to, what courses to take, specific jargon and language used on campus, professors to network with, and more. Being the first in your family to attend higher education can be daunting, shocking, confusing, lonely and incredibly inimidating and white students who benefit from legacy preference do not encounter those challenges. Ultimately, white students also do not have to exist under the crushing weight of racism in a country that constantly tries to harm them.

Teaching at Metropolitan Detention Center: Part 2

This week I share some of my final thoughts after finishing teaching one course at the Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC). If you haven’t read my first newsletter on this topic where I recount my initial experience in detail and share some background of Just Ideas, the program I am working with to teach these classes, please check it out here before reading on. Honestly friends, this experience has been full of far more joy than I could have ever imagined. Merely engaging with these men, witnessing them, hearing them, validating their experiences, I believe, is the true work. Human Rights begins with seeing the humanity in those who are most vulnerable, most marginalized, most forgotten. Before meeting my group of 15, I already felt immense empathy for this community, but after engaging with these men, my heart absolutely breaks for each one of them. I am firmly and unequivocally an abolitionist. I believe mass incarceration is an unnecessary evil and it has been proven that locking human being away does not reduce crime and absolutely does not rehabilitate those who have committed crimes.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 56 of this newsletter. This week I share some of my final thoughts after finishing one course at the Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC). If you haven’t read my first newsletter on this topic where I recount my initial experience in detail and share some background of Just Ideas, the program I am working with to teach these classes, please check it out. Honestly friends, this experience has been full of far more joy than I could have ever imagined. Merely engaging with these men, witnessing them, hearing them, validating their experiences, I believe, is the true work. Human Rights begins with seeing the humanity in those who are most vulnerable, most marginalized, most forgotten. I believe mass incarceration is an unnecessary evil and it has been proven that locking human being away does not reduce crime and absolutely does not rehabilitate those who have committed crimes. These are some of my big takeaways after the course. Let’s get into it!

Lets Get Into It

On May 31, I started a mini-course at MDC Brooklyn with a group of 15 men, led by Professor Christia Mercer. After finishing the course this week, there are a few key takeaways that I know will stay with me throughout my career in Human Rights and in mass incarceration research and reform.

1. It’s not important why someone is incarcerated

I’m not a lawyer. My job isn’t to defend anyone, place judgement on their actions or analyze their decisions. Whatever reason someone is incarcerated is none of my business. Statistically, there could very well be someone that is innocent or was coerced into a false confession in one of my classes—and even that is none of my business. There are a few reasons why this is true. The most important, in my opinion, is because acting on any information that might be shared with me would jeopardize my ability to ever work or volunteer in a federal prison again. Following the rules means not discussing someone’s specific case or becoming overly involved and it’s vital that I do so in order to continue this work. Above all, I believe in restorative justice. I believe that our current prison system has no place in a society. If I believe that truly, I must do the work I wish existed. I must treat each of the people I come in contact with with grace, kindness and respect, or else, what am I really doing? I’ve actually found it easy not to care about why someone might be in my class, but engage with them as they are and hope my small impact on their experience while incarcerated will be a positive one.

2. It’s not my job to save anyone

One of my acting teachers growing up said I had a “soft heart”. I always loved the picture that painted in my mind. Going inside, I think having a soft heart allows me to operate from a place of kindness. It allows me the ability to understand how dire the circumstances are for a human being who is locked in a cage and largely forgotten by our society. While this softness helps me to connect with people, I also understand it cannot become my entire personality when I’m inside. These men are in class to learn, many of them wanting to receive college credit and eventually go on to receiving advanced degrees. My time inside isn’t a pity party for them or for me. My job is to be a decent human being and help these men learn the material, nothing more.

3. The relationship formed between myself and the students is a reciprocal one, not a hierarchical one

I learned so much while being a part of this class. The men in the program come from so many diverse backgrounds, educations and experiences and I quickly realized how limited the perspectives have been in the rooms I have learned in throughout my life. Hearing them share their thoughts on the play, on philosophy, on how something in the text from 2,500 years ago might connect to our lives today, taught me so much. “Diversity” is always championed in the workplace and in schools as a meaningful tool to enrich the education process. I was able to experience how true that can be when surrounded by people who had lived through some very different circumstances than I have. The class isn’t about me looking down at them from my ivory tower of academia, but looking eye to eye as much as we can (while understanding the simple inequality that I get to leave at the end of class and they do not).

4. The experience is not scary

I was actually most nervous about just getting inside of the prison. The dress codes, regulations and the thought of contact with corrections officers were all really intimidating. To my suprise, the officers I engaged with shook my hand or even gave me a hug. They were glad to have us. They valued the program and the impact is has had. It was confusing. I still don’t know how to fully make sense of the way in which I chatted with prison staff while walking through heavy doors and metal detectors. Once inside, I felt truly and oddly safe. The men were warm and eager to learn. They were complex and unique and brough different things to each and every class. They were incredibly funny and willing to participate in icebreakers and games without much hesitation. They were engaging and serious. They were thoughtful and patient with one another, with themselves, with me. These men broke my heart wide open. I felt immense sadness knowing these few weeks were the extent of my contact with them, but immense joy in having known them. I was never afraid.

5. Prisons should not exist

My biggest takeaway is that prisons should not exist. Prisons only further perpetuate racism, inequality and injustice. Human beings do not belong in cages and every single person innately deserves dignity. According to the US Department of Justice, “Prisons are good for punishing criminals and keeping them off the street, but prison sentences (particularly long sentences) are unlikely to deter future crime. Prisons actually may have the opposite effect.” They go on to say the severity of punishment, including implementing the death penalty, does little to deter crime. Prisons do not rehabilitate those who have committed crimes. Prisons do not keep everyday Americans safer because they do not deter criminal activity. What prisons are successful at is both spending millions and making millions, punishing people, perpetuating high rates of recidivism, impacting Black Americans as disproportionately high levels and creating a free labor force of enslaved workers.

Friends, in the coming weeks I look forward to sharing more with you about Just Ideas as I continue with the program as well as opening up a conversation on abolition. Be well, see ya next time!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Affirmative Action: Part 1

Today, June 29, the Supreme Court struck down college affirmative action programs. This week’s topic: Affirmative Action . A conservative supermajority in the Supreme Court upending decades of jurisprudence when they decided that race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina are unconstitutional. This decision has many implications, including the potential to change the way that college admission processes are handled, and the potential to have a ripple effect that impacts the business world and corporate sector.

Hi Friends,

Welcome to Issue 55 of this newsletter. Today, June 29, the Supreme Court struck down college affirmative action programs. This week’s topic: Affirmative Action . A conservative supermajority in the Supreme Court upending decades of jurisprudence when they decided that race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard and the University of North Carolina are unconstitutional. This decision has many implications, including the potential to change the way that college admission processes are handled, and the potential to have a ripple effect that impacts the business world and corporate sector. The two cases were brought by Students for Fair Admissions, a group founded by Edward Blum. Blum is not a lawyer. According to a New York Times profile, “he is a one-man legal factory with a growing record of finding plaintiffs who match his causes, winning big victories and trying above all to erase racial preferences from American life”. He has orchestrated more than two dozen lawsuits challenging affirmative action practices and voting rights laws across the country. Rachel Kleinman, senior counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, said that Mr. Blum’s opposition to affirmative action was related to “this fear of white people that their privilege is being taken away from them and given to somebody else who they see as less deserving.” At its core, affirmative action is not the practice of giving Black and Latinx students priority during college admission. While people like Edward Blum ignore the historical backdrop of the American experience and reduce establish policies to feelings over facts, today we will learn the truth about what affirmative action really is, how it came to be, and why it has been an important—albeit imperfect—part of the admissions process.

After beginning to research the history and impact of affirmative action, I’ve decided to divide this newsletter into two. Today, we will discuss the history and background of affirmative action. Next time, we will discuss the impact and implications of affirmative action and the most recent Supreme Court decision. Let’s get into it.

Key Words

“Strict Scrutiny” : The Court calls for "strict scrutiny" in determining whether discrimination existed before implementing a federal affirmative action program. "Strict scrutiny" meant that affirmative action programs fulfilled a "compelling governmental interest," and were "narrowly tailored" to fit the particular situation. To pass the strict scrutiny test, a law must be narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest. The same test applies whether the racial classification aims to benefit or harm a racial group. Strict scrutiny also applies whether or not race is the only criteria used to classify.

“Race Neutral”: “Race neutral” does not appear in the opinion of the court, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, which states that colleges and universities have “concluded, wrongly, that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned but the color of their skin.” But when Roberts clarifies that students can still refer to their race in admissions essays, explaining challenges they’ve overcome, he and the majority are buying into the idea of race neutrality. Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote his own concurring opinion, uses the term “race neutral” repeatedly, offering it as an antidote to affirmative action.

Supreme Court Opinion: The term “opinions” refers to several types of writing by the Justices. The most well-known opinions are those released or announced in cases in which the Court has heard oral argument. Each opinion sets out the Court’s judgment and its reasoning and may include the majority or principal opinion as well as any concurring or dissenting opinions.

Executive Order: An executive order is a signed, written, and published directive from the President of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. They are numbered consecutively, so executive orders may be referenced by their assigned number, or their topic.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Provisions of this civil rights act forbade discrimination on the basis of sex, as well as, race in hiring, promoting, and firing. The Act prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and federally funded programs. It also strengthened the enforcement of voting rights and the desegregation of schools.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act: As amended, Title VII protects employees and job applicants from employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission: The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is responsible for enforcing federal laws that make it illegal to discriminate against a job applicant or an employee because of the person's race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy and related conditions, gender identity, and sexual orientation), national origin, age (40 or older), disability or genetic information. Most employers with at least 15 employees are covered by EEOC laws (20 employees in age discrimination cases). Most labor unions and employment agencies are also covered. The laws apply to all types of work situations, including hiring, firing, promotions, harassment, training, wages, and benefits.

Equal Protection Clause: The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment ensures that all Americans receive equal protection under the Constitution. Both the majority and the minority opinions in Thursday’s ruling cited the clause, using different interpretations. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that race-based admissions programs “cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause,” while Sonia Sotomayor wrote in a dissent that the decision “subverts the constitutional guarantee of equal protection by further entrenching racial inequality in education.”

Lets Get Into It

Affirmative action, as a term, came to the fore in 1935 with the Wagner Act, a federal law that gave workers the right to form and join unions. But John F. Kennedy was the first president to link the term specifically with a policy meant to advance racial equality, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

On March 6, 1961 President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10925, which included a provision that government contractors "take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin." The intent of this executive order was to affirm the government's commitment to equal opportunity for all qualified persons, and to take positive action to strengthen efforts to realize true equal opportunity for all. This executive order was superseded by Executive Order 11246 in 1965.

So, where exactly are we in history in 1961 when it comes to the rights of Black Americans?

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery in 1865, 96 years prior

To put this in context, if a Black American lived to be around 100, they would have lived through being a slave and also been alive when President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10925. Most Black Americans at this time would have parents and grandparents who were slaves when President John F. Kennedy issued Executive Order 10925.

The first “Jim Crow Law” is passed in Tennessee mandating the separation of African Americans from whites on trains in 1870, 91 years prior

Plessy v. Ferguson established the “separate but equal” doctrine that allows segregation, discrimination and racism to flourish in 1896, 65 years prior

Jackie Robinson became the first Black American in the twentieth century to play baseball in the major leagues in 1947, 14 years prior

Brown v. Board of education which desegregated public schools was in 1954, 7 years prior

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott took place in 1955, 6 years prior

The Civil Rights Act, which extended civil, political, and legal rights and protections to Black Americans, including former slaves and their descendants, and put an end segregation in public and private facilities was in 1964, 3 years after

The Voting Rights Act, which allowed all Americans access to the polls was in 1965, 4 years after

Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated in 1968, 7 years after

The History of Affirmative Action

1961: The first use of the term “affirmative action” specifically with a policy meant to advance racial equality is in Executive Order 10925, as discussed above.

1961: The “Plan for Progress” is signed by Vice President Johnson and Courtlandt Gross, the president of Lockheed

NAACP labor secretary Herbert Hill filed complaints against the hiring and promoting practices of Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. Lockheed was doing business with the Defense Department on the first billion-dollar contract. Due to taxpayer-funding being 90% of Lockheed's business, along with disproportionate hiring practices, Black workers charged Lockheed with "overt discrimination." Lockheed signed an agreement with Vice President Johnson that pledged an "aggressive seeking out for more qualified minority candidates for technical and skill positions.” Soon, other defense contractors signed similar voluntary agreements. However, most corporations in the south, still ruled by Jim Crow Laws, ignored the recommendations.

1964: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

Note that this same act was used to continue discrimination. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had limited the type of remedies possible by forbidding any form of discrimination. This was interpreted to include preferential hiring, which was seen as compensatory discrimination. To put it plainly — folks found a way to reason that giving Black workers preferential treatment by hiring them with an emphasis on their race could be considered discriminatory in and of itself.

1964: The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) was created by Congress in 1964 to enforce Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, as amended, protects employees and job applicants from employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

1965: President Lyndon B. Johnson issued Executive Order 11246, prohibiting employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, and national origin by those organizations receiving federal contracts and subcontracts. This executive order requires federal contractors to take affirmative action to promote the full realization of equal opportunity for women and minorities. The Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP), under the Department of Labor, monitors this requirement for all federal contractors, including all UC campuses. Compliance with these regulations (for ederal contractors employing more than 50 people and having federal contracts totaling more than $50,000) includes disseminating and enforcing a nondiscrimination policy, establishing a written affirmative action plan and placement goals for women and minorities, and implementing action-oriented programs for accomplishing these goals.

1967: President Johnson amended Executive Order 11246 to also include sex.

“The contractor will not discriminate against any employee or applicant for employment because of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The contractor will take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Such action shall include, but not be limited to the following: employment, upgrading, demotion, or transfer; recruitment or recruitment advertising; layoff or termination; rates of pay or other forms of compensation; and selection for training, including apprenticeship.”

1969: The Philadelphia Plan was implemented by Richard Nixon. For the first time, a specific industry was required to articulate a plan for hiring minority workers. The Nixon administration created specific hiring goals in the highly segregated construction industry. The Philadelphia Plan required Philadelphia government contractors in six construction trades to set goals and timetables for the hiring of minority workers or risk losing the valuable contracts. No quotas were set. This left businesses a fair amount of autonomy in determining how to meet the goals. As a result, the Philadelphia Plan withstood a court challenge and growing public hostility to affirmative action.

1969: Colleges voluntarily adopted similar policies to combat racial discrimination. In 1969, many elite universities admitted more than twice as many Black students as they had the year before. This change was directly linked to the civil rights movement. With civil rights activists urging schools to admit more Black applicants, colleges responded. Higher education had been almost exclusively white for most of its history, but a growing number of universities were now crafting affirmative action policies in an effort to expand access to higher education.

1974: Marco DeFunis Jr. v. Odegaard — Marco DeFunis, a white man, argued that he was denied admission to the University of Washington Law School because the school had prioritized admitting minority students who were less qualified, saying that this violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. By the time the United States Supreme Court considered the case, DeFunis was already in his last year of law school and the court ruled that the case was moot. Though the court chose not to address the issues within the case, it was the first case heard on affirmative action since the policy was established in the 1960s.

1978: Regents of the University of California v. Bakke — Alan Bakke was rejected twice from the medical school at the University of California, Davis. Mr. Bakke, who is white, argued that the school’s affirmative action policy to reserve 16 out of 100 spots for qualified minority students violated the equal protection clause as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Supreme Court ruled that the racial quota system used by the university did violate the Civil Rights Act and that Mr. Bakke should be admitted. Justice Lewis F. Powell acknowledged in his opinion that a state had legitimate interests in considering the race of applicants, and that a diverse student body could provide compelling educational benefits. The case established the court’s position on affirmative action for decades. A state university had to meet a standard of judicial review known as strict scrutiny: Race could be a narrowly tailored factor in admissions policies. Racial quotas, however, went too far.

1980: Fullilove v. Klutznick —While Bakke struck down strict quotas, in Fullilove the Supreme Court ruled that some modest quotas were perfectly constitutional. The Court upheld a federal law requiring that 15% of funds for public works be set aside for qualified minority contractors. The "narrowed focus and limited extent" of the affirmative action program did not violate the equal rights of non-minority contractors, according to the Court—there was no "allocation of federal funds according to inflexible percentages solely based on race or ethnicity."

1983: Reagan signed Executive Order 12432. The executive order requires that each federal agency with grant making capabilities establish an Annual Minority Business Development Plan with the stated goal to increase minority business participation. Agencies are expected to establish programs that assist minority business enterprises to procure contracts and manage those contracts awarded. As a stipulation of the executive order, the progress toward these goals is to be annually reported to the Secretary of Commerce. While the Reagan administration opposed discriminatory practices, it did not support the implementation of quotas and goals and did not support Executive Order 11246. Bi-partisan opposition in Congress and other government officials blocked the repeal of Executive Order 11246 but he reduced funding for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, arguing that "reverse discrimination" resulted from these policies.

1997: Proposition 209 was enacted in California, which is a state ban on all forms of affirmative action: "The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting." Proposed in 1996, the controversial ban had been delayed in the courts for almost a year before it went into effect. Over the past three decades, 10 states have banned affirmative action in college admissions. And in many cases, voters approved those bans.

1998: Washington becomes the second state to abolish state affirmative action measures when it passed "I 200," which is similar to California's Proposition 209.

2000: Florida legislature approves education component of Gov. Jeb Bush's "One Florida" initiative, aimed at ending affirmative action in the state.

2003: Grutter v. Bollinger — Barbara Grutter, a white woman who was denied admission to the University of Michigan Law School, said that the school had used race as a predominant factor for admitting students. When the case reached the Supreme Court, a 5-4 opinion led by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor upheld the Bakke decision. The Court ruled that each admissions decision is based on multiple factors, and that the school could fairly use race as one of them. The case reaffirmed the court’s position that diversity on campus is a compelling state interest.

2003: Gratz v. Bollinger — Though decided on the same day and focused on the same university, the Gratz case and Grutter case had different outcomes. Jennifer Gratz and Patrick Hamacher, both white, were denied admission to the University of Michigan. They argued that a point system in use by the admissions office beginning in 1998 was unconstitutional. Students who were part of an underrepresented minority group automatically received 20 points in a system that required 100 points for admittance, which meant that nearly every applicant of an underrepresented minority group was admitted. In a 6-3 opinion led by Justice William H. Rehnquist, the Supreme Court ruled that the point system did not meet the standards of strict scrutiny established in previous cases. The Grutter and Gratz cases provided a blueprint for how schools could use race as a factor in admissions policies. The Court held that the OUA’s policies were not sufficiently narrowly tailored to meet the strict scrutiny standard. Because the policy did not provide individual consideration, but rather resulted in the admission of nearly every applicant of “underrepresented minority” status, it was not narrowly tailored in the manner required by previous jurisprudence on the issue.

2006: Meredith v. Jefferson — Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS) were integrated by court order until 2000. After its release from the order, JCPS implemented an enrollment plan to maintain substantial racial integration. Students were given a choice of schools, but not all schools could accommodate all applicants. In those cases, student enrollment was decided on the basis of several factors, including place of residence, school capacity, and random chance, as well as race. However, no school was allowed to have an enrollment of black students less than 15% or greater than 50% of its student population. The District Court ruled that the plan was constitutional because the school had a compelling interest in maintaining racial diversity.

2006: Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 — The Seattle School District allowed students to apply to any high school in the District. Since certain schools often became oversubscribed when too many students chose them as their first choice, the District used a system of tiebreakers to decide which students would be admitted to the popular schools. The second most important tiebreaker was a racial factor intended to maintain racial diversity. At a particular school either whites or non-whites could be favored for admission depending on which race would bring the racial balance closer to the goal. A non-profit group, Parents Involved in Community Schools (Parents), sued the District, arguing that the racial tiebreaker violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Washington state law. A federal District Court dismissed the suit, upholding the tiebreaker. On appeal, a three-judge panel the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit reversed. By a 5-4 vote, the Court applied a "strict scrutiny" framework and found the District's racial tiebreaker plan unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This was a major setback for affirmative action.

2016: Fisher v. University of Texas (Two Cases) — Abigail Fisher, a white woman who was rejected from the University of Texas, said that the school’s two-part admissions system, which takes race into consideration, is unconstitutional. The university first admits roughly the top 10 percent of every in-state graduating high school class, a policy known as the Top Ten Percent Plan, and then reviews several factors, including race, to fill the remaining spots. Upon a second review of the case by the Supreme Court, a 4-3 opinion led by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy ruled that the university’s policy met the standard of strict scrutiny, meaning this was okay for the school to do.

Affirmative Action in Colleges and Universities

If you’re like me, you’re reading through this timeline and thinking that a lot of these policies seem directly aimed at businesses, while there’s no clear law that might ask a college or university to do something specific in regards to affirmative action. Affirmative action in colleges and universities was not enacted through a specific federal law, but rather through a series of executive orders and court rulings. Executive Order 10925 in 1961 and Executive Order 11246 in 1965 are cited when discussing affrimative action in schooling. The Supreme Court case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978 upheld the constitutionality of affirmative action in a university setting. Since then, there have been ongoing debates and legal challenges regarding the implementation of affirmative action in college admissions. The policies and specific requirements for affirmative action have varied across states and institutions, with some implementing more extensive programs than others. However, affirmative action as a concept has been recognized and practiced by many colleges and universities throughout the country. Personally, I’m always surprised by the ways laws work in the United States. From what we hear and see on the news, you would imagine schools were being forced to meet quotas (which is actually unconstitutional) or do something really specific and widespread, but thats completely not the case.

So, what positive impact has affirmative action had on colleges and universities?

Affirmative action has played a crucial role in fostering diversity on college campuses. By considering race or ethnicity as one factor among many in the admissions process, universities have been able to create more inclusive environments that reflect the broader society. It also seeks to address historical and ongoing inequalities by providing equal opportunities for underrepresented groups, such as Black Americans, Latinx Americans, and Indigenous peoples. It acknowledges that systemic barriers and discrimination have limited access to education for certain communities, and aims to level the playing field by considering the broader context in which applicants' achievements and qualifications are evaluated. Affirmative action has also helped mitigate the impact of unconscious biases that can influence the admissions process. Unconscious biases, often shaped by societal stereotypes, can unintentionally favor certain groups while disadvantaging others. By explicitly considering race or ethnicity, universities can counteract these biases and ensure fairer evaluations. Affirmative action also contributes to breaking down stereotypes and reducing isolation on college campuses. It helps create environments where students can engage with diverse peers, challenge stereotypes, and build relationships based on shared experiences and understanding. Affirmative action has been essential tool for advancing diversity and equal opportunity in higher education. Reports have shown that schools that once implemented affirmative action policies experience a massive drop in Black and Latinx students when those policies are changed. Without affirmative action, schools will surely become more white and less diverse.

The most noteworthy and compelling piece of the affirmative action conversation, in my opinion is the concept that affirmative action is an inherently unequal policy alongside the inescapable fact that historic inequalities exist in America. The truth is, there are so many ways in which everyday Americans are afforded certain privileges in education, business, housing, funding, and nearly every facet of life. It is noteworthy that affirmative action is often attacked when these other areas are not. The next newsletter will discuss some of these concepts along with more reactions to the most recent Supreme Court decision. See ya then.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Teaching at Metropolitan Detention Center

This week I started my internship at Just Ideas, a program through the Center for New Narratives in Philosophy at Columbia University and founded by Christia Mercer. I wanted to document the experience in as much detail as possible. I feel a responsibility to this role and a responsibility to the men in my class. Even though I am still trying to find the language to describe how impactful this experience has been for me, I wanted to share it here, with you.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 54 of this newsletter. This week I’ll be opening up about my experience teaching at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn. Yesterday, I went into the prison for the first time through Columbia University’s Just Ideas internship. Today, I’m reflecting on the experience, preparing for upcoming classes, and trying to find the language to discuss this next phase of my work. Let’s get into it.

Lets Get Into It

Just Ideas is a program within the Center for New Narratives in Philosophy at Columbia University. Founded by Christia Mercer, Gustav Berne Professor of Philosophy, the program brings together professors and interns to engage with people in New York prisons. By discussing some of the most challenging literature there is, we reflect on profound philosophical questions like the role of love and suffering in life and the nature of justice and wisdom. We encourage each other to become more reflective agents in the world. In fall 2014, Geraldine Downey, Director of Columbia's Center for Justice, asked Christia to be the first senior professor to teach in Columbia's new Justice-in-Education Initiative — this is how Just Ideas was born. In 2015, Professor Mercer wrote this op-ed for the Washington Post. I’ll pull some information from that piece throughout this newsletter, but want to offer an insight that she shares:

“The pleasures I’ve found teaching in prison are among the richest I’ve ever had. But the pleasure I find in this pedagogical delight is matched by the pain of recognition that my students’ intellectual exploration will cease without volunteers like me. We must not allow so many members of our community to languish in prison without the chance for intellectual development. We must find it in ourselves to educate all Americans.”

My experience at MDC or Metropolitan Detention Center in the Sunnyside neighborhood of Brooklyn is absolutely one of the richest experience I have had. I was lucky enough to teach alongside Professor Mercer this Wednesday and will be teaching alongside her for the rest of this course, which is truly an experience that I know will impact me for the rest of my life. Before diving deeper into my personal experience at MDC, here’s a little more backround on the prison system and it’s intersection with eduction from that 2015 op-ed:

“There are roughly 2.2 million people in a correctional facility in the United States, which incarcerates more individuals than any other country in the world. According to a 2012 study, 58.5 percent of incarcerated people are black or Latino. According to the Sentencing Project, one in three black men will be incarcerated.

Although more than 50 percent of people in these facilities have high school diplomas or a GED, most prisons offer little if any post-secondary education.

Things have not always been this bad. In the 1980’s, when the prison population sat below 400,000, our incarcerated citizens were educated through state and federal funding. But the 1990’s brought an abrupt end to government support. When President Clinton signed into law the Crime Bill in 1994, he eliminated incarcerated people’s eligibility for federal Pell grants and sentenced a generation of incarcerated Americans to educational deprivation. Nationwide, over 350 college programs in prisons were shut down that year. Many states jumped on the tough-on-crime bandwagon and slashed state funded prison educational programs. In New York State, for example, no state funds can be used to support secondary-education in prison. Before 1994, there were 70 publicly funded post-secondary prison programs in the state. Now there are none. In many states across the country, college instruction has fallen primarily to volunteers.”

“There are hundreds of thousands of students just like mine scattered across the country eager to be educated and keen to join the ranks of active participants in our democracy.

As a society, we owe them (and ourselves) that chance. A National Institute of Justice study has found that 76.6 percent of formerly incarcerated people return to prison within five years of release.

According to research by the Rand Institute, recidivism goes down by 43 percent when people are offered education.

Those who leave prison with a college degree are much more likely to gain employment, be role models for their own children (50 percent of incarcerated adults have children), and become active members of their communities. Some of my students are quite clear about the desire to motivate their children: “the conversation changes when you’re educating yourself.””

May 31, 2023

Upon entering MDC, I exchanged my license for a key to a small silver locker. I put my belongings inside and made my way to be screened and scanned. I wore my husband’s jeans, since tight clothing isn’t allowed, and a plain purple T-shirt. Many clothing items are restricted, and I wanted to ensure I had no issues. I took off my sneakers and put them in a bin with my copy of Sophocles’s Antigone and my key. I walked into a hallway with many elevators. We piled in with a few other workers and officers, everyone seeming to be in good spirits. If I’m honest, it wasn’t what I expected, not that I knew what to expect. I tried really hard to have no expectations. I pushed out all of the articles I’ve read and honestly barely thought about what it would be like to enter MDC the entire week leading up to it.

We walked out of the elevator into the Chapel, where chairs sat in a semicircle. We set down our stack of folders and waited. Fifteen men entered in brown jumpsuits, copies of Antigone in hand. I was nervous, and I couldn’t really articulate why. Many people asked me if I felt scared or hesitant to go to prison, and the truth is that I never did, and I still didn’t at that moment. I have known and trusted and loved people who have been incarcerated—but even if I hadn’t, these men deserve an opportunity to learn from someone who sees them without judgment or fear. I felt capable of doing that.

Professor Mercer introduced herself; she wanted them to know that we weren’t the “B Team”; we were qualified, smart, top-tier instructors from a competitive Ivy League University. She wanted them to know they were worth learning from someone like her. Someone like me (even though Professor Mercer is like 100000 times more qualified). We started out with a game. “Say your name and something you love. I want you to dig deep and be honest. When you shake someone’s hand, you suddenly become them, you take on their name and what they love, and then you introduce yourself like that to the next person.” I gave the class the instructions and told them to stand up and start walking around the room. (Coming from a theatre background, I have done this hundreds of times in my life. “Walk around the space,” my acting teachers used to say at the start of almost every class.) Everyone started laughing, trying to remember who they were embodying and what that person loved. Some people said things like “cars” or “food”. Others said things like “my daughter” or “justice” or “freedom.” Eventually, the game ended, and we all sat down, feeling a little lighter.

Soon, we dove into the book. The big questions about justice and law and rules and love. We talked about moral universalism and moral relativism. We read the text out loud. I did a dramatic reading of a few of the big monologues at the start of the play, and I felt like my entire body was being filled up with light. We divided the class into small groups, some defending Ismene and some defending Antigone, and I walked around and gave advice and support to each group. The class debated, and folks who seemed sleepy and disinterested for the first half of class started becoming impassioned and immersed in the conversation. We gave them an assignment for the next class: turning this debate into a short essay and writing a Haiku that connected to the text. I fist-bumped a few of the men and wrote down recommendations they gave me on books to read. I told them we would talk about them next week.

Three hours later, an officer came in the room to escort us out and bring the men back—I don’t even know where?—but back. They packed into the elevator, and I waved. I smiled. I said, “Don’t forget to write your Haikus guys!” and they laughed and either nodded or said some version of, “We will, we will.” The officer remarked, “That’s definitely the first time anyone’s ever yelled that in a prison”. I said, “And I hope it’s not the last!”

I write this all down because I don’t want to forget a thing. The way these men, whom I had only met three hours before, lingered in the room, stacking chairs, jotting down notes from the board, remarking that class flew by…I don’t want to forget those moments. I feel a responsibility to remember.

I’m trying to find the right words to describe this experience’s impact on me. I wonder if it’s okay for me to even be thinking about “me” right now. I want to bring as much respect and humanity, and dignity to these men as I possibly can.

When I interviewed Professor Joy James a few months ago, she described her work as an activist and an academic, stating the ways in which we must not look down from the ivory tower of academia on those we fight for and with, but on as equal terms as we can. Eye to eye, we ask them, “so what do we do?”. My hope in joining this program was to ask myself if I could do this work as an activist, an academic, an abolitionist. I know now, with certainty, that I can. I know now that I will.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Stop and Frisk

Stop and frisk was up for debate in the 1968 Terry v. Ohio supreme court case which found it to be legal, and set this precedent: “Under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may stop a suspect on the street and frisk him or her without probable cause to arrest…” Stop and frisk historically has targeted Black and Latinx New Yorkers, let’s talk about it.

Hi Friends!

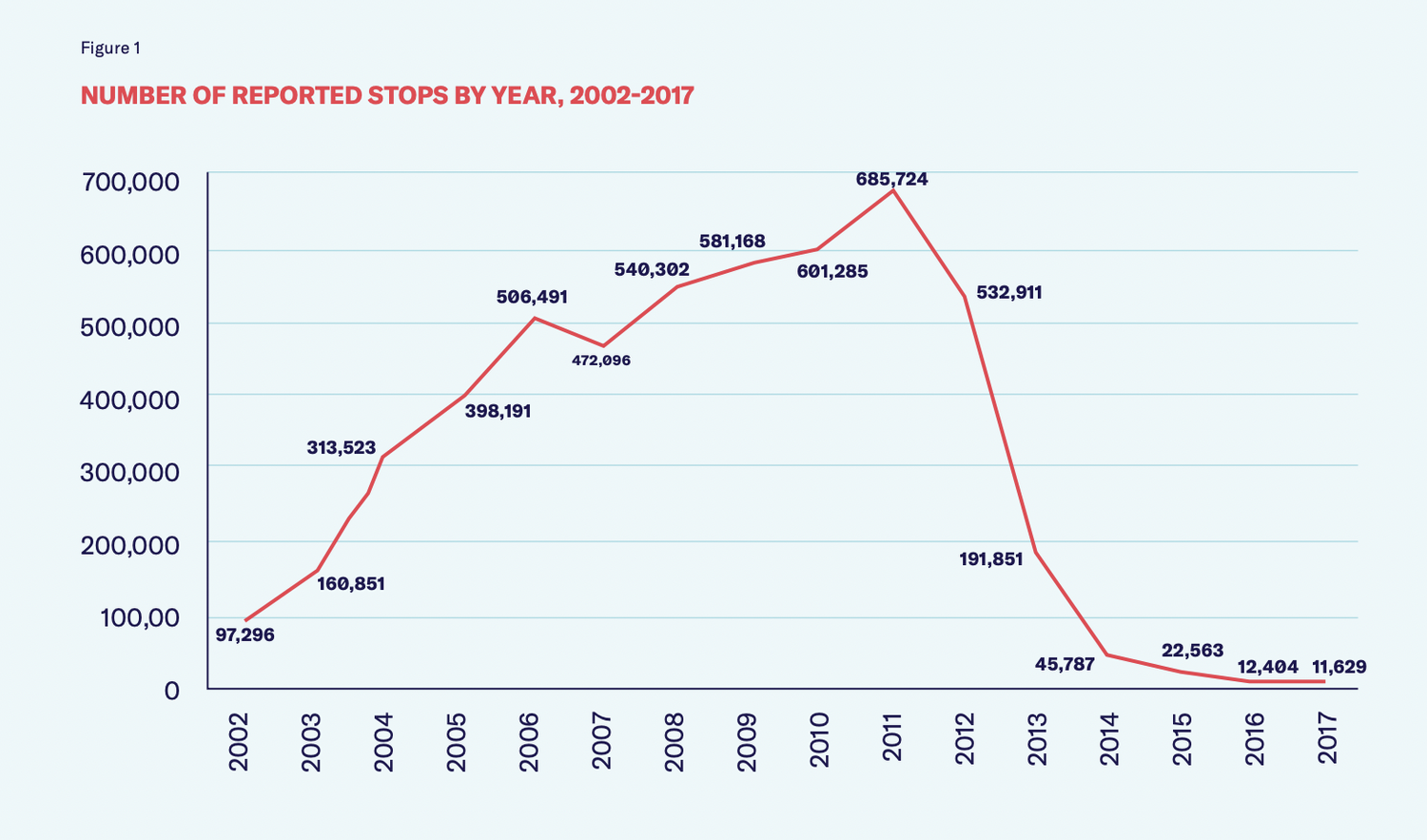

Welcome to Issue 53 of this newsletter. This week’s topic is: Stop and Frisk. I was inspired to write on this topic from some of my reading for a class I’m taking at Columbia called “Human Rights in the United States”. Stop and frisk was up for debate at the 1968 Terry v. Ohio supreme court case which found it to be legal, and set this precedent: “Under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may stop a suspect on the street and frisk him or her without probable cause to arrest, if the police officer has a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime and has a reasonable belief that the person ‘may be armed and presently dangerous.’" Outside of New York, this practice is known as a Terry Stop, based on the name of the case. However, in 2013, in Floyd v. City of New York, US District Court Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that stop-and-frisk had been used in an unconstitutional manner due to racial profiling and directed the police to adopt a written policy to specify where such stops are authorized. Stop and frisk was a signature policy of the Bloomberg administration beginning in 2002 and reaching its peak in 2011 with over 600,000 incidents that year alone. A . According to a highly researched study by the NYCLU, “over 97 percent of all stops that occurred from 2003-2021 took place during [Bloomberg’s] time in office.” Stop and frisk never reduced crime, but always took a toll of Black and Latinx communities. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Stop and frisk: The controversial policy allowed police officers to stop, interrogate and search New York City citizens on the sole basis of “reasonable suspicion.”

Terry v. Ohio: A Cleveland detective (McFadden), on a downtown beat which he had been patrolling for many years, observed two strangers (petitioner and another man, Chilton) on a street corner. Suspecting the two men of "casing a job, a stick-up," the officer followed them and saw them rejoin the third man a couple of blocks away in front of a store. The officer approached the three, identified himself as a policeman, spun petitioner around, patted down his outside clothing, and found in his overcoat pocket, but was unable to remove, a pistol. . The court distinguished between an investigatory "stop" and an arrest, and between a "frisk" of the outer clothing for weapons and a full-blown search for evidence of crime. Under the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a police officer may stop a suspect on the street and frisk him or her without probable cause to arrest, if the police officer has a reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime and has a reasonable belief that the person "may be armed and presently dangerous."

Floyd v. City of New York: The Center for Constitutional Rights filed the federal class action lawsuit Floyd, et al. v. City of New York, et al. against the City of New York to challenge the New York Police Department’s practices of racial profiling and unconstitutional stop and frisks of New York City residents. The named plaintiffs in the case – David Floyd, David Ourlicht, Lalit Clarkson, and Deon Dennis – represent the thousands of primarily Black and Latino New Yorkers who have been stopped without any cause on the way to work or home from school, in front of their house, or just walking down the street. In a historic ruling on August 12, 2013, following a nine-week trial, a federal judge found the New York City Police Department liable for a pattern and practice of racial profiling and unconstitutional stops. Floyd focuses not only on the lack of any reasonable suspicion to make these stops, in violation of the Fourth Amendment, but also on the obvious racial disparities in who is stopped and searched by the NYPD.

Broken Windows Theory: Kelling and Wilson suggested that a broken window or other visible signs of disorder or decay — think loitering, graffiti, prostitution or drug use — can send the signal that a neighborhood is uncared for. So, they thought, if police departments addressed those problems, maybe the bigger crimes wouldn't happen. Stop and frisk was seen as a way of managing this. Kelling and Wilson proposed that police departments change their focus. Instead of channeling most resources into solving major crimes, they should instead try to clean up the streets and maintain order — such as keeping people from smoking pot in public and cracking down on subway fare beaters. If broken windows meant arresting people for misdemeanors in hopes of preventing more serious crimes, "stop and frisk" said, why even wait for the misdemeanor? Why not go ahead and stop, question and search anyone who looked suspicious? In Chicago, the researchers Robert Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush analyzed what makes people perceive social disorder. They found that if two neighborhoods had exactly the same amount of graffiti and litter and loitering, people saw more disorder, more broken windows, in neighborhoods with more African-Americans.

Let’s Get Into It

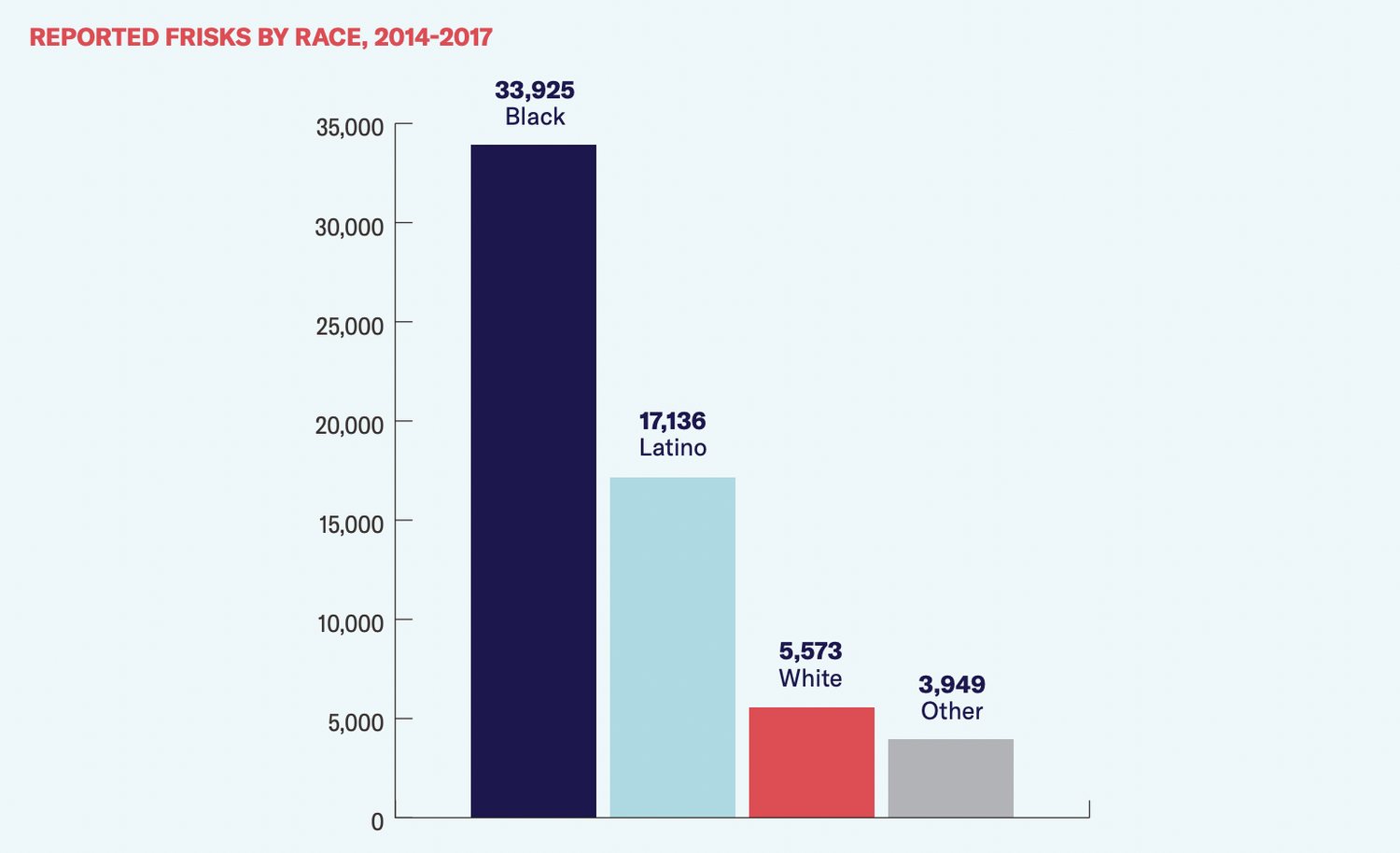

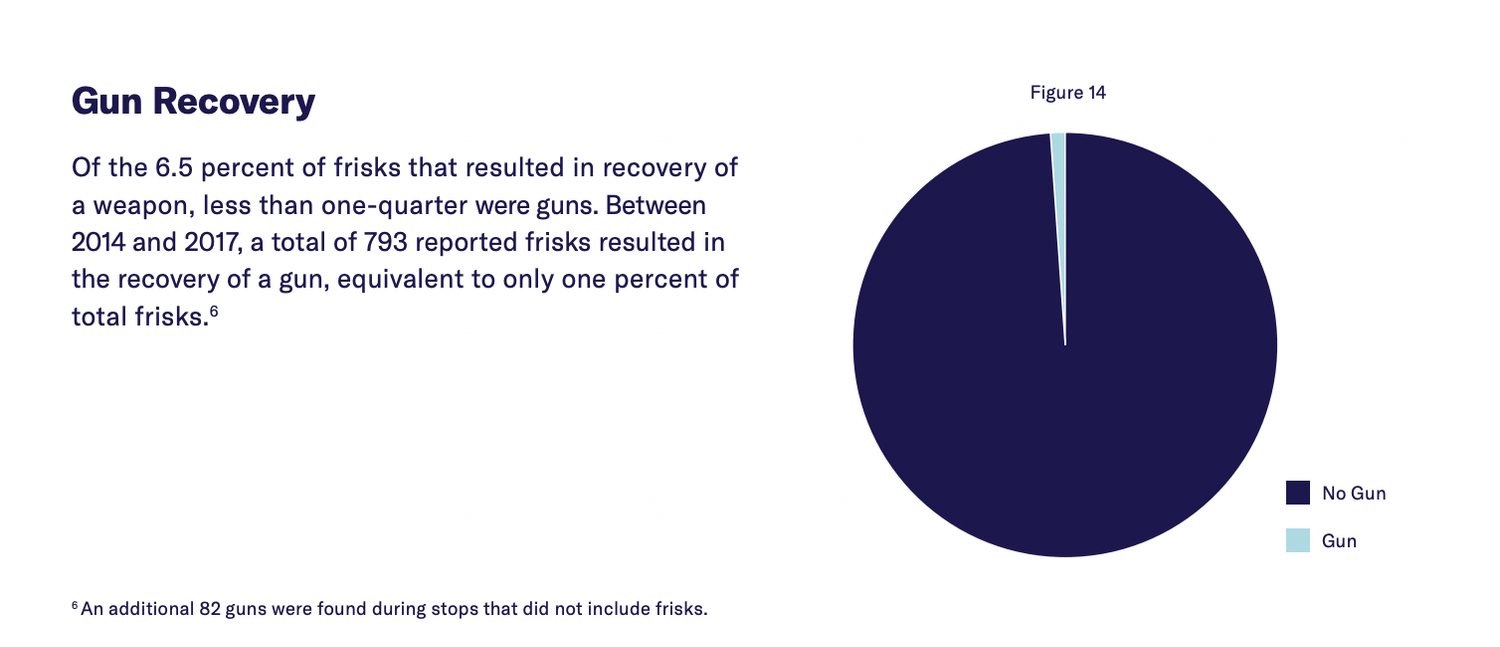

A 2019 report by NYCLU on Stop and Frisk encapsulated so much relevant information to how this system has operated in New York City, so all of the info below will be pulled from there.

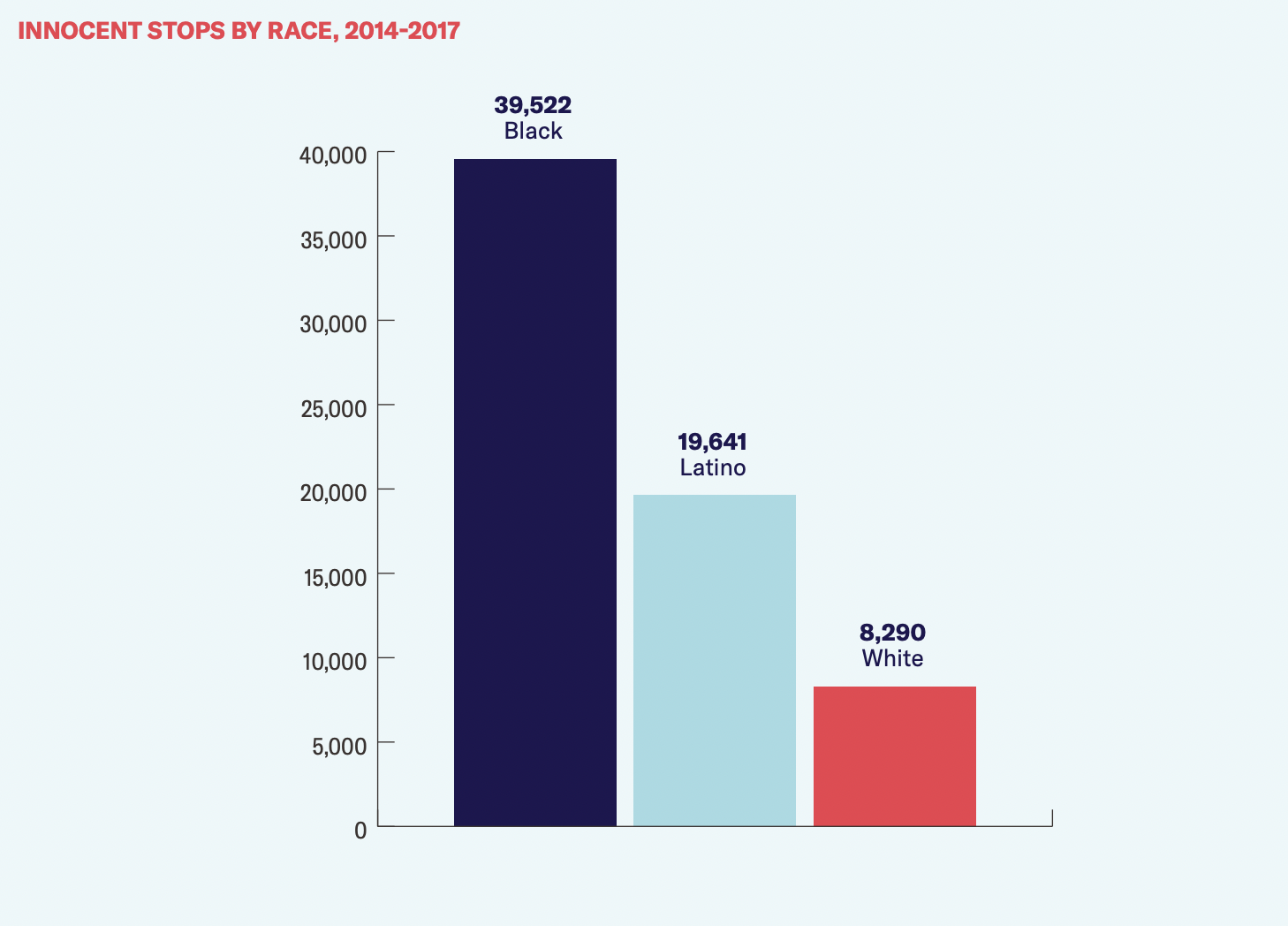

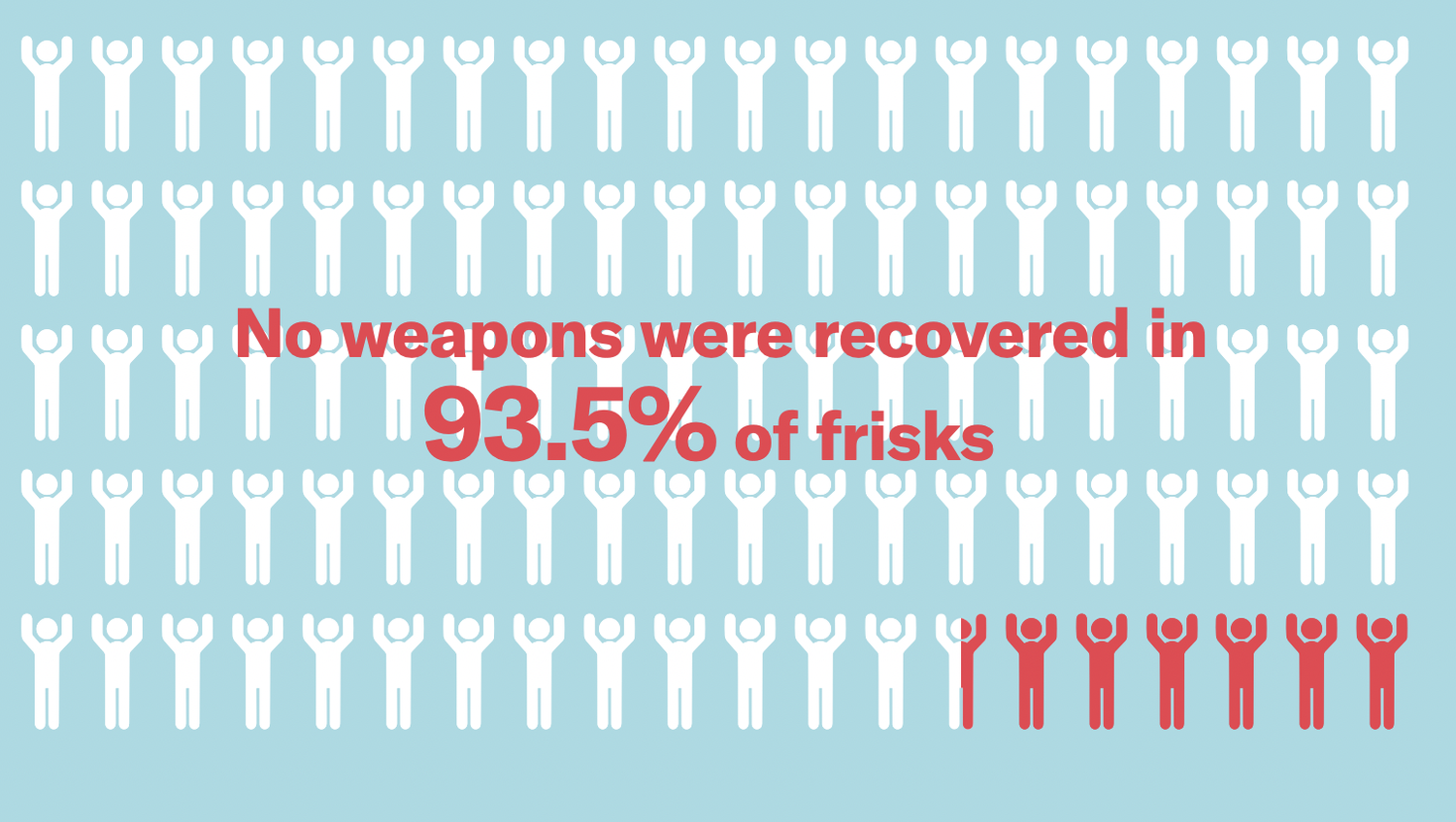

The New York City Police Department’s aggressive stop-and-frisk program exploded into a national controversy during the mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg, as the number of NYPD stops each year grew to hundreds of thousands. Most of the people stopped were black and Latino, and nearly all were innocent. Stop-and-frisk peaked in 2011, when NYPD officers made nearly 700,000 stops.

It is notable that “actions of engaging in a violent crime” was a reason listed in only seven percent of reported stops between 2014 and 2016. During the height of stop-and-frisk, the NYPD routinely argued that the disproportionate number of stops of Black people was justified because, according to the department, Black people are disproportionately involved in violent crimes. Given that over 90 percent of stops had nothing to do with a suspected violent crime, the race of those convicted of violent crimes generally cannot explain the disproportionate number of Black people stopped every year

Stops of Males Age 14-24

24.9% (22,998) Young Black Males but only 1.9% (158,406) of NYC’s population

12.8% (11,193) Young Latino Males but only 2.8% (226,677) of NYC’s population

In 2011, 685,724 NYPD stops were recorded — this is at the peak of Stop and Frisk under Bloomberg

605,328 were innocent (88 percent).

350,743 were Black (53 percent).

223,740 were Latinx (34 percent).

61,805 were white (9 percent).

In 2021, 8,947 stops were recorded.

5,422 were innocent (61 percent).

5,404 were Black (60 percent).

2,457 were Latinx (27 percent).

732 were white (8 percent).

192 were Asian / Pacific Islander (2 percent)

71 were Middle Eastern/Southwest Asian (1 percent)

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

2019 Bail Reform Law

In short, this law virtually eliminated bail for the most common, non-violent crimes, and reduced our jail populations by over 30%. By April of 2020, however, due to fearmongering and unsubstantiated claims made by groups like the NYPD, 12 crimes had their new bail policies rolled back, rendering the original law virtually useless. Remember — bail criminalizes poverty.

Hello Friends!

Happy New Year and welcome back, this is Issue 52!

I’m so excited to share that I finished my first semester at Columbia with a 4.0! For my final paper, I wrote about the 2019 bail reform law in New York. In short, this law virtually eliminated bail for the most common, non-violent crimes, and reduced our jail populations by over 30%. By April of 2020, however, due to fearmongering and unsubstantiated claims made by groups like the NYPD, 12 crimes had their new bail policies rolled back, rendering the original law virtually useless.

Remember — bail criminalizes poverty.

This is how the jail system works: you are accused of a crime or potentially found in a position that seems suspicious, you’re taking to jail, you brought before a judge for arraignment, the judge decides if you are allowed to post bail before your trial or not and sets an amount, the bail is due immediately. If you are unable to pay bail, you stay in jail to await trial. (Jail is a temporary space for shorter sentences and those that cannot pay bail, prison is for longer sentences after your trial has occurred). Take note that you are in jail while you await trial, meaning, you are still not sentenced at this time. In Rikers Island, one of New York’s most notorious jails, only 10% are released within 24 hours, while 25% stay locked up awaiting trial for two months or longer. If these individuals could afford to pay bail, many would be home with their families, continuing to work and live their lives during these months.

Kalief Browder was held at Rikers for three years from 2010-2013, spending over two of those years in solitary confinement — after being accused of stealing a backpack, a crime which he plead “not-guilty” to. His trial was delayed by a backlog of work at the Bronx County District Attorney's office. Eventually the case was dismissed after Browder experienced irreparable mental, emotional and physical abuse. He eventually died by suicide in 2015 after suffering from his trauma. He said while being in jail “I feel like I was robbed of my happiness.”

The money-driven bail system in America is inhuman, unjust and blatantly criminalizes poverty — which is inextricably tied to race in America. If you want to learn more about the 2019 bail reform in New York through a human rights lens, check out my final paper below.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Cash Bail

When someone is accused of a crime, a judge decides if they are 1) held without bail, 2) released, 3) held with bail. If someone cannot pay bail, they go to jail. This is before they have a trial. Every day, nearly half a million individuals sit in local jails who have not been convicted of any crime. Why are most of them there? Because they cannot afford cash bail. To avoid this, many people plead guilty and take a plea deal instead of waiting for a trail. Only about 5% of cases go to trial at all. This has lasting consequences. Bail criminalizes poverty.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 51 newsletter. This week’s topic is: The Cash Bail System in America. First and foremost, we should establish what bail is and how it’s used. The terms “jail” and “prison” are often used interchangeably, but they actually are two separate institutions. A jail is for short-term sentences, or where someone waits for trial. A prison is for a long-term sentence, including a life sentence. There are other differences between jails and prisons in terms of who oversees them, what the incarcerated person can access, potential resources and more. In 2019, there were “1,566 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 2,850 local jails, 1,510 juvenile correctional facilities, 186 immigration detention facilities, and 82 Indian country jails, as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.” When someone is accused of a crime, a judge decides if they are 1) held without bail, 2) released, 3) held with bail. If someone cannot pay bail, they go to jail. This is before they have a trial. Every day, nearly half a million individuals sit in local jails who have not been convicted of any crime. Why are most of them there? Because they cannot afford cash bail. In 2014, only 14% of New Yorkers could afford to pay their bail, meaning 86% of those accused of a crime were sitting in jails for days, weeks, or even years. To avoid this, many people plead guilty and take a plea deal instead of waiting for a trail. Only about 5% of cases go to trial at all. This has lasting consequences. Bail criminalizes poverty. Let’s get into it.

Key Terms

Bail: Cash bail is a refundable, court-determined fee that a defendant pays—regardless of guilt or innocence—to await trial at home instead of in jail. While “innocent until proven guilty” is ingrained in the American psyche, the use of bail means that if you can’t pay you serve jail time.

Bond: The words “bail” and “bond” are often used almost interchangeably when discussing jail release, and while they are closely related to each other, they are not the same thing. Bail is the money a defendant must pay in order to get out of jail. A bond is posted on a defendant’s behalf, usually by a bail bond company, to secure his or her release.

Bail Schedule: A bail schedule is a list of bail amount recommendations for different charges. Some states allow defendants to post bail with the police before they go to their first court appearance. The required amount of bail will depend on the crime that the defendant allegedly committed. A key difference between police bail schedules and bail determinations by judges is that a judge has discretion to alter the amount. They can consider many different factors, such as a defendant’s criminal history, employment status, and ties to the community. These intangible factors do not affect the bail schedule in a jail. If you are unwilling to pay the amount required by the bail schedule, you likely will need to go to court and present your case to a judge.

Plea Deal: Plea deals—which are entirely within the discretion of a prosecutor to offer (or accept)—typically include one or more of the following: 1) the dismissal of one or more charges, and/or agreement to a conviction to a lesser offense, 2) an agreement to a more lenient sentence and length, 3) an agreement to stipulate to a version of events that omits certain facts that would statutorily expose a person to harsher penalties.

Criminal Conviction: Besides direct consequences that can include jail time, fines, and treatment, a criminal conviction can trigger many consequences outside of the criminal court system. These consequences can affect your current job, future job opportunities, housing choices, immigration status. You may have to disclose your criminal record to employers. You may find it difficult to obtain a mortgage, auto loan, business loan, or other loan due to your criminal conviction. While a conviction does not automatically eliminate your eligibility for financial aid for college, it could impact on your ability to qualify. Landlords often conduct background checks before approving a prospective tenant and may not approve you for housing. In some states, you could lose your right to vote, serve on a jury, or hold a public office if you are convicted of a felony. Your conviction could have serious implications for your immigration status. Even a misdemeanor conviction can limit your ability to travel to other countries. You may lose custody of your children.

Risk Assessments: Developed and implemented by a mix of jurisdictions, states, private companies, nonprofit organizations and academic institutions, these special algorithms use factors such as age, education level, arrest record and home address to assign scores to defendants. Risk assessment tools are marketed as a way to automate a resource-strapped system and remove human bias. But critics say that they can amplify existing inequities, especially against young Black and Latino men and people experiencing mental illness. More than 60 percent of Americans live in a jurisdiction where the risk assessment tools are in use, according to Mapping Pretrial Injustice, a nonprofit data campaign critical of the tools.

The 8th Amendment: Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Let’s Get Into It

Fast Facts About Bail

COVID-19 has exacerbated bail issues and led to longer stays in jail for people who have yet to have a trial. In New York, for example, for people who do not make bail, average jail stays have become longer. The average number of days people were in custody in New York City jails rose from 198.4 in January 2020, or roughly six and a half months, to 286.5 days, or more than nine months, in August 2021 – a 44% increase.

The average length of pretrial incarceration in the US is 26 days

At any given time an estimated half a million Americans, or about two-thirds of the overall jail population, are incarcerated because they can’t afford their bail or a bond.

About 94% of felony convictions at the state level and about 97% at the federal level are the result of plea bargains. That means only 3%-6% of all cases actually go to trial.

Why Does Bail Exist And How Does It Work?

From The Marshall Project:

You’ve been arrested, taken to jail, fingerprinted and processed. Within 24 to 48 hours, you’ll go to an initial hearing known as an arraignment.

There, a judge will formally present the charges against you, and you will plead innocent or guilty. Then the judge either grants bail and sets the amount; releases you on your own recognizance without a fee; or denies you bail.

Bail is usually denied if a defendant is deemed a flight risk or a danger to the community because of the nature of the alleged crime.

If you get bail, you have three choices:

Pay the amount in full and get out of jail. You’ll get the money back when the trial is over, no matter the outcome.

Pay nothing. You’ll return to jail and await trial.

Secure a bail bond and get out of jail. In this case, you’ll pay a private agent known as a bondsman a portion of the amount, usually 10 percent and collateral such as a home or jewelry to cover the balance. (In turn, bail bond companies guarantee the full amount to the court.) The fee you pay for a bail bond is not refundable, even if your charges are dropped.

Resources

Friends, the bail system is absolutely horrific, and this is just scratching the surface.

I plan on discussing bail a lot more in this newsletter since it’s something I’m focusing a lot of thought on in school. This newsletter is just the start so I wanted to cover the basics. My final paper for one of my classes will center around bail, specifically as it impacts New Yorkers. Bail is absolutely heinous and destroys people’s lives. Let’s keep talking about it. See ya next week!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Human Rights

You probably know by now that I’m pursuing a masters degree from Columbia University in Human Rights Studies from the Institute for the Study of Human Rights. You might be wondering what that means. For a lot of us, we think of human rights as an umbrella term, a vague topic that covers a lot of different things. Racism, discrimination, homophobia, poverty, addiction, mental illness, refugee status — these might be some topics that pop into our heads when we think of human rights. But what exactly are capital H, capital R, Human Rights?

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 50 of our newsletter. This week’s topic is: What Are Human Rights? You probably know by now that I’m pursuing a masters degree from Columbia University in Human Rights Studies from the Institute for the Study of Human Rights. You might be wondering what that means. For a lot of us, we think of human rights as an umbrella term, a vague topic that covers a lot of different things. Racism, discrimination, homophobia, poverty, addiction, mental illness, refugee status — these might be some topics that pop into our heads when we think of human rights. But what exactly are capital H, capital R, Human Rights? It’s actually a very specific area of study, let’s get into it!

Key Terms