Weekly Anti-racism NewsletteR

Because it ain’t a trend, honey.

-

Taylor started her newsletter in 2020 and has been the sole author of almost one hundred blog mosts and almost two hundred weekly emails. A lifelong lover of learning, Taylor began researching topics of interest around anti-racism education and in a personal effort to learn more about all marginalized groups. When friends asked her to share her learnings, she started sending brief email synopsises with links to her favorite resources or summarizing her thoughts on social media. As the demand grew, she made a formal platform to gather all of her thoughts and share them with her community. After accumulating thousands of subscribers and writing across almost one hundred topics, Taylor pivoted from weekly newsletters to starting a podcast entitled On the Outside. Follow along with the podcast to learn more.

-

This newsletter covers topics from prison reform to colorism to supporting the LGBTQ+ community. Originally, this was solely a newsletter focused on anti-racism education, but soon, Taylor felt profoundly obligated to learn and share about all marginalized communities. Taylor seeks guidance from those personally affected by many of the topics she writes about, while always acknowledging the ways in which her own privilege shows up.

Teaching at Metropolitan Detention Center: Part 2

This week I share some of my final thoughts after finishing teaching one course at the Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC). If you haven’t read my first newsletter on this topic where I recount my initial experience in detail and share some background of Just Ideas, the program I am working with to teach these classes, please check it out here before reading on. Honestly friends, this experience has been full of far more joy than I could have ever imagined. Merely engaging with these men, witnessing them, hearing them, validating their experiences, I believe, is the true work. Human Rights begins with seeing the humanity in those who are most vulnerable, most marginalized, most forgotten. Before meeting my group of 15, I already felt immense empathy for this community, but after engaging with these men, my heart absolutely breaks for each one of them. I am firmly and unequivocally an abolitionist. I believe mass incarceration is an unnecessary evil and it has been proven that locking human being away does not reduce crime and absolutely does not rehabilitate those who have committed crimes.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 56 of this newsletter. This week I share some of my final thoughts after finishing one course at the Metropolitan Detention Center (MDC). If you haven’t read my first newsletter on this topic where I recount my initial experience in detail and share some background of Just Ideas, the program I am working with to teach these classes, please check it out. Honestly friends, this experience has been full of far more joy than I could have ever imagined. Merely engaging with these men, witnessing them, hearing them, validating their experiences, I believe, is the true work. Human Rights begins with seeing the humanity in those who are most vulnerable, most marginalized, most forgotten. I believe mass incarceration is an unnecessary evil and it has been proven that locking human being away does not reduce crime and absolutely does not rehabilitate those who have committed crimes. These are some of my big takeaways after the course. Let’s get into it!

Lets Get Into It

On May 31, I started a mini-course at MDC Brooklyn with a group of 15 men, led by Professor Christia Mercer. After finishing the course this week, there are a few key takeaways that I know will stay with me throughout my career in Human Rights and in mass incarceration research and reform.

1. It’s not important why someone is incarcerated

I’m not a lawyer. My job isn’t to defend anyone, place judgement on their actions or analyze their decisions. Whatever reason someone is incarcerated is none of my business. Statistically, there could very well be someone that is innocent or was coerced into a false confession in one of my classes—and even that is none of my business. There are a few reasons why this is true. The most important, in my opinion, is because acting on any information that might be shared with me would jeopardize my ability to ever work or volunteer in a federal prison again. Following the rules means not discussing someone’s specific case or becoming overly involved and it’s vital that I do so in order to continue this work. Above all, I believe in restorative justice. I believe that our current prison system has no place in a society. If I believe that truly, I must do the work I wish existed. I must treat each of the people I come in contact with with grace, kindness and respect, or else, what am I really doing? I’ve actually found it easy not to care about why someone might be in my class, but engage with them as they are and hope my small impact on their experience while incarcerated will be a positive one.

2. It’s not my job to save anyone

One of my acting teachers growing up said I had a “soft heart”. I always loved the picture that painted in my mind. Going inside, I think having a soft heart allows me to operate from a place of kindness. It allows me the ability to understand how dire the circumstances are for a human being who is locked in a cage and largely forgotten by our society. While this softness helps me to connect with people, I also understand it cannot become my entire personality when I’m inside. These men are in class to learn, many of them wanting to receive college credit and eventually go on to receiving advanced degrees. My time inside isn’t a pity party for them or for me. My job is to be a decent human being and help these men learn the material, nothing more.

3. The relationship formed between myself and the students is a reciprocal one, not a hierarchical one

I learned so much while being a part of this class. The men in the program come from so many diverse backgrounds, educations and experiences and I quickly realized how limited the perspectives have been in the rooms I have learned in throughout my life. Hearing them share their thoughts on the play, on philosophy, on how something in the text from 2,500 years ago might connect to our lives today, taught me so much. “Diversity” is always championed in the workplace and in schools as a meaningful tool to enrich the education process. I was able to experience how true that can be when surrounded by people who had lived through some very different circumstances than I have. The class isn’t about me looking down at them from my ivory tower of academia, but looking eye to eye as much as we can (while understanding the simple inequality that I get to leave at the end of class and they do not).

4. The experience is not scary

I was actually most nervous about just getting inside of the prison. The dress codes, regulations and the thought of contact with corrections officers were all really intimidating. To my suprise, the officers I engaged with shook my hand or even gave me a hug. They were glad to have us. They valued the program and the impact is has had. It was confusing. I still don’t know how to fully make sense of the way in which I chatted with prison staff while walking through heavy doors and metal detectors. Once inside, I felt truly and oddly safe. The men were warm and eager to learn. They were complex and unique and brough different things to each and every class. They were incredibly funny and willing to participate in icebreakers and games without much hesitation. They were engaging and serious. They were thoughtful and patient with one another, with themselves, with me. These men broke my heart wide open. I felt immense sadness knowing these few weeks were the extent of my contact with them, but immense joy in having known them. I was never afraid.

5. Prisons should not exist

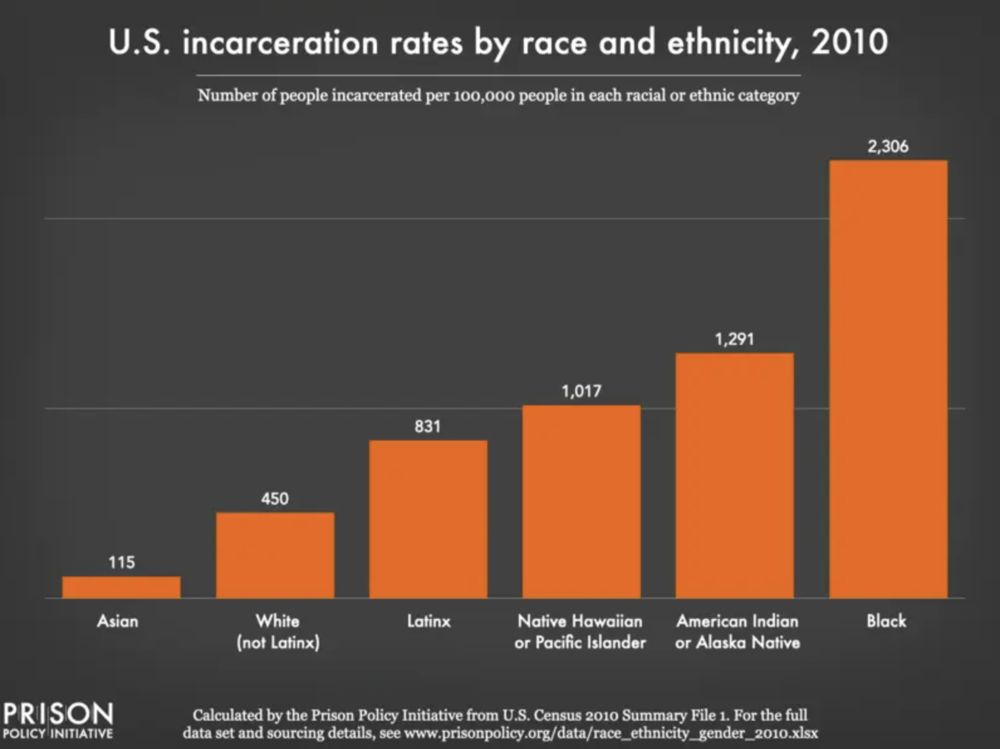

My biggest takeaway is that prisons should not exist. Prisons only further perpetuate racism, inequality and injustice. Human beings do not belong in cages and every single person innately deserves dignity. According to the US Department of Justice, “Prisons are good for punishing criminals and keeping them off the street, but prison sentences (particularly long sentences) are unlikely to deter future crime. Prisons actually may have the opposite effect.” They go on to say the severity of punishment, including implementing the death penalty, does little to deter crime. Prisons do not rehabilitate those who have committed crimes. Prisons do not keep everyday Americans safer because they do not deter criminal activity. What prisons are successful at is both spending millions and making millions, punishing people, perpetuating high rates of recidivism, impacting Black Americans as disproportionately high levels and creating a free labor force of enslaved workers.

Friends, in the coming weeks I look forward to sharing more with you about Just Ideas as I continue with the program as well as opening up a conversation on abolition. Be well, see ya next time!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Teaching at Metropolitan Detention Center

This week I started my internship at Just Ideas, a program through the Center for New Narratives in Philosophy at Columbia University and founded by Christia Mercer. I wanted to document the experience in as much detail as possible. I feel a responsibility to this role and a responsibility to the men in my class. Even though I am still trying to find the language to describe how impactful this experience has been for me, I wanted to share it here, with you.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 54 of this newsletter. This week I’ll be opening up about my experience teaching at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn. Yesterday, I went into the prison for the first time through Columbia University’s Just Ideas internship. Today, I’m reflecting on the experience, preparing for upcoming classes, and trying to find the language to discuss this next phase of my work. Let’s get into it.

Lets Get Into It

Just Ideas is a program within the Center for New Narratives in Philosophy at Columbia University. Founded by Christia Mercer, Gustav Berne Professor of Philosophy, the program brings together professors and interns to engage with people in New York prisons. By discussing some of the most challenging literature there is, we reflect on profound philosophical questions like the role of love and suffering in life and the nature of justice and wisdom. We encourage each other to become more reflective agents in the world. In fall 2014, Geraldine Downey, Director of Columbia's Center for Justice, asked Christia to be the first senior professor to teach in Columbia's new Justice-in-Education Initiative — this is how Just Ideas was born. In 2015, Professor Mercer wrote this op-ed for the Washington Post. I’ll pull some information from that piece throughout this newsletter, but want to offer an insight that she shares:

“The pleasures I’ve found teaching in prison are among the richest I’ve ever had. But the pleasure I find in this pedagogical delight is matched by the pain of recognition that my students’ intellectual exploration will cease without volunteers like me. We must not allow so many members of our community to languish in prison without the chance for intellectual development. We must find it in ourselves to educate all Americans.”

My experience at MDC or Metropolitan Detention Center in the Sunnyside neighborhood of Brooklyn is absolutely one of the richest experience I have had. I was lucky enough to teach alongside Professor Mercer this Wednesday and will be teaching alongside her for the rest of this course, which is truly an experience that I know will impact me for the rest of my life. Before diving deeper into my personal experience at MDC, here’s a little more backround on the prison system and it’s intersection with eduction from that 2015 op-ed:

“There are roughly 2.2 million people in a correctional facility in the United States, which incarcerates more individuals than any other country in the world. According to a 2012 study, 58.5 percent of incarcerated people are black or Latino. According to the Sentencing Project, one in three black men will be incarcerated.

Although more than 50 percent of people in these facilities have high school diplomas or a GED, most prisons offer little if any post-secondary education.

Things have not always been this bad. In the 1980’s, when the prison population sat below 400,000, our incarcerated citizens were educated through state and federal funding. But the 1990’s brought an abrupt end to government support. When President Clinton signed into law the Crime Bill in 1994, he eliminated incarcerated people’s eligibility for federal Pell grants and sentenced a generation of incarcerated Americans to educational deprivation. Nationwide, over 350 college programs in prisons were shut down that year. Many states jumped on the tough-on-crime bandwagon and slashed state funded prison educational programs. In New York State, for example, no state funds can be used to support secondary-education in prison. Before 1994, there were 70 publicly funded post-secondary prison programs in the state. Now there are none. In many states across the country, college instruction has fallen primarily to volunteers.”

“There are hundreds of thousands of students just like mine scattered across the country eager to be educated and keen to join the ranks of active participants in our democracy.

As a society, we owe them (and ourselves) that chance. A National Institute of Justice study has found that 76.6 percent of formerly incarcerated people return to prison within five years of release.

According to research by the Rand Institute, recidivism goes down by 43 percent when people are offered education.

Those who leave prison with a college degree are much more likely to gain employment, be role models for their own children (50 percent of incarcerated adults have children), and become active members of their communities. Some of my students are quite clear about the desire to motivate their children: “the conversation changes when you’re educating yourself.””

May 31, 2023

Upon entering MDC, I exchanged my license for a key to a small silver locker. I put my belongings inside and made my way to be screened and scanned. I wore my husband’s jeans, since tight clothing isn’t allowed, and a plain purple T-shirt. Many clothing items are restricted, and I wanted to ensure I had no issues. I took off my sneakers and put them in a bin with my copy of Sophocles’s Antigone and my key. I walked into a hallway with many elevators. We piled in with a few other workers and officers, everyone seeming to be in good spirits. If I’m honest, it wasn’t what I expected, not that I knew what to expect. I tried really hard to have no expectations. I pushed out all of the articles I’ve read and honestly barely thought about what it would be like to enter MDC the entire week leading up to it.

We walked out of the elevator into the Chapel, where chairs sat in a semicircle. We set down our stack of folders and waited. Fifteen men entered in brown jumpsuits, copies of Antigone in hand. I was nervous, and I couldn’t really articulate why. Many people asked me if I felt scared or hesitant to go to prison, and the truth is that I never did, and I still didn’t at that moment. I have known and trusted and loved people who have been incarcerated—but even if I hadn’t, these men deserve an opportunity to learn from someone who sees them without judgment or fear. I felt capable of doing that.

Professor Mercer introduced herself; she wanted them to know that we weren’t the “B Team”; we were qualified, smart, top-tier instructors from a competitive Ivy League University. She wanted them to know they were worth learning from someone like her. Someone like me (even though Professor Mercer is like 100000 times more qualified). We started out with a game. “Say your name and something you love. I want you to dig deep and be honest. When you shake someone’s hand, you suddenly become them, you take on their name and what they love, and then you introduce yourself like that to the next person.” I gave the class the instructions and told them to stand up and start walking around the room. (Coming from a theatre background, I have done this hundreds of times in my life. “Walk around the space,” my acting teachers used to say at the start of almost every class.) Everyone started laughing, trying to remember who they were embodying and what that person loved. Some people said things like “cars” or “food”. Others said things like “my daughter” or “justice” or “freedom.” Eventually, the game ended, and we all sat down, feeling a little lighter.

Soon, we dove into the book. The big questions about justice and law and rules and love. We talked about moral universalism and moral relativism. We read the text out loud. I did a dramatic reading of a few of the big monologues at the start of the play, and I felt like my entire body was being filled up with light. We divided the class into small groups, some defending Ismene and some defending Antigone, and I walked around and gave advice and support to each group. The class debated, and folks who seemed sleepy and disinterested for the first half of class started becoming impassioned and immersed in the conversation. We gave them an assignment for the next class: turning this debate into a short essay and writing a Haiku that connected to the text. I fist-bumped a few of the men and wrote down recommendations they gave me on books to read. I told them we would talk about them next week.

Three hours later, an officer came in the room to escort us out and bring the men back—I don’t even know where?—but back. They packed into the elevator, and I waved. I smiled. I said, “Don’t forget to write your Haikus guys!” and they laughed and either nodded or said some version of, “We will, we will.” The officer remarked, “That’s definitely the first time anyone’s ever yelled that in a prison”. I said, “And I hope it’s not the last!”

I write this all down because I don’t want to forget a thing. The way these men, whom I had only met three hours before, lingered in the room, stacking chairs, jotting down notes from the board, remarking that class flew by…I don’t want to forget those moments. I feel a responsibility to remember.

I’m trying to find the right words to describe this experience’s impact on me. I wonder if it’s okay for me to even be thinking about “me” right now. I want to bring as much respect and humanity, and dignity to these men as I possibly can.

When I interviewed Professor Joy James a few months ago, she described her work as an activist and an academic, stating the ways in which we must not look down from the ivory tower of academia on those we fight for and with, but on as equal terms as we can. Eye to eye, we ask them, “so what do we do?”. My hope in joining this program was to ask myself if I could do this work as an activist, an academic, an abolitionist. I know now, with certainty, that I can. I know now that I will.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

2019 Bail Reform Law

In short, this law virtually eliminated bail for the most common, non-violent crimes, and reduced our jail populations by over 30%. By April of 2020, however, due to fearmongering and unsubstantiated claims made by groups like the NYPD, 12 crimes had their new bail policies rolled back, rendering the original law virtually useless. Remember — bail criminalizes poverty.

Hello Friends!

Happy New Year and welcome back, this is Issue 52!

I’m so excited to share that I finished my first semester at Columbia with a 4.0! For my final paper, I wrote about the 2019 bail reform law in New York. In short, this law virtually eliminated bail for the most common, non-violent crimes, and reduced our jail populations by over 30%. By April of 2020, however, due to fearmongering and unsubstantiated claims made by groups like the NYPD, 12 crimes had their new bail policies rolled back, rendering the original law virtually useless.

Remember — bail criminalizes poverty.

This is how the jail system works: you are accused of a crime or potentially found in a position that seems suspicious, you’re taking to jail, you brought before a judge for arraignment, the judge decides if you are allowed to post bail before your trial or not and sets an amount, the bail is due immediately. If you are unable to pay bail, you stay in jail to await trial. (Jail is a temporary space for shorter sentences and those that cannot pay bail, prison is for longer sentences after your trial has occurred). Take note that you are in jail while you await trial, meaning, you are still not sentenced at this time. In Rikers Island, one of New York’s most notorious jails, only 10% are released within 24 hours, while 25% stay locked up awaiting trial for two months or longer. If these individuals could afford to pay bail, many would be home with their families, continuing to work and live their lives during these months.

Kalief Browder was held at Rikers for three years from 2010-2013, spending over two of those years in solitary confinement — after being accused of stealing a backpack, a crime which he plead “not-guilty” to. His trial was delayed by a backlog of work at the Bronx County District Attorney's office. Eventually the case was dismissed after Browder experienced irreparable mental, emotional and physical abuse. He eventually died by suicide in 2015 after suffering from his trauma. He said while being in jail “I feel like I was robbed of my happiness.”

The money-driven bail system in America is inhuman, unjust and blatantly criminalizes poverty — which is inextricably tied to race in America. If you want to learn more about the 2019 bail reform in New York through a human rights lens, check out my final paper below.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Cash Bail

When someone is accused of a crime, a judge decides if they are 1) held without bail, 2) released, 3) held with bail. If someone cannot pay bail, they go to jail. This is before they have a trial. Every day, nearly half a million individuals sit in local jails who have not been convicted of any crime. Why are most of them there? Because they cannot afford cash bail. To avoid this, many people plead guilty and take a plea deal instead of waiting for a trail. Only about 5% of cases go to trial at all. This has lasting consequences. Bail criminalizes poverty.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 51 newsletter. This week’s topic is: The Cash Bail System in America. First and foremost, we should establish what bail is and how it’s used. The terms “jail” and “prison” are often used interchangeably, but they actually are two separate institutions. A jail is for short-term sentences, or where someone waits for trial. A prison is for a long-term sentence, including a life sentence. There are other differences between jails and prisons in terms of who oversees them, what the incarcerated person can access, potential resources and more. In 2019, there were “1,566 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 2,850 local jails, 1,510 juvenile correctional facilities, 186 immigration detention facilities, and 82 Indian country jails, as well as in military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in the U.S. territories.” When someone is accused of a crime, a judge decides if they are 1) held without bail, 2) released, 3) held with bail. If someone cannot pay bail, they go to jail. This is before they have a trial. Every day, nearly half a million individuals sit in local jails who have not been convicted of any crime. Why are most of them there? Because they cannot afford cash bail. In 2014, only 14% of New Yorkers could afford to pay their bail, meaning 86% of those accused of a crime were sitting in jails for days, weeks, or even years. To avoid this, many people plead guilty and take a plea deal instead of waiting for a trail. Only about 5% of cases go to trial at all. This has lasting consequences. Bail criminalizes poverty. Let’s get into it.

Key Terms

Bail: Cash bail is a refundable, court-determined fee that a defendant pays—regardless of guilt or innocence—to await trial at home instead of in jail. While “innocent until proven guilty” is ingrained in the American psyche, the use of bail means that if you can’t pay you serve jail time.

Bond: The words “bail” and “bond” are often used almost interchangeably when discussing jail release, and while they are closely related to each other, they are not the same thing. Bail is the money a defendant must pay in order to get out of jail. A bond is posted on a defendant’s behalf, usually by a bail bond company, to secure his or her release.

Bail Schedule: A bail schedule is a list of bail amount recommendations for different charges. Some states allow defendants to post bail with the police before they go to their first court appearance. The required amount of bail will depend on the crime that the defendant allegedly committed. A key difference between police bail schedules and bail determinations by judges is that a judge has discretion to alter the amount. They can consider many different factors, such as a defendant’s criminal history, employment status, and ties to the community. These intangible factors do not affect the bail schedule in a jail. If you are unwilling to pay the amount required by the bail schedule, you likely will need to go to court and present your case to a judge.

Plea Deal: Plea deals—which are entirely within the discretion of a prosecutor to offer (or accept)—typically include one or more of the following: 1) the dismissal of one or more charges, and/or agreement to a conviction to a lesser offense, 2) an agreement to a more lenient sentence and length, 3) an agreement to stipulate to a version of events that omits certain facts that would statutorily expose a person to harsher penalties.

Criminal Conviction: Besides direct consequences that can include jail time, fines, and treatment, a criminal conviction can trigger many consequences outside of the criminal court system. These consequences can affect your current job, future job opportunities, housing choices, immigration status. You may have to disclose your criminal record to employers. You may find it difficult to obtain a mortgage, auto loan, business loan, or other loan due to your criminal conviction. While a conviction does not automatically eliminate your eligibility for financial aid for college, it could impact on your ability to qualify. Landlords often conduct background checks before approving a prospective tenant and may not approve you for housing. In some states, you could lose your right to vote, serve on a jury, or hold a public office if you are convicted of a felony. Your conviction could have serious implications for your immigration status. Even a misdemeanor conviction can limit your ability to travel to other countries. You may lose custody of your children.

Risk Assessments: Developed and implemented by a mix of jurisdictions, states, private companies, nonprofit organizations and academic institutions, these special algorithms use factors such as age, education level, arrest record and home address to assign scores to defendants. Risk assessment tools are marketed as a way to automate a resource-strapped system and remove human bias. But critics say that they can amplify existing inequities, especially against young Black and Latino men and people experiencing mental illness. More than 60 percent of Americans live in a jurisdiction where the risk assessment tools are in use, according to Mapping Pretrial Injustice, a nonprofit data campaign critical of the tools.

The 8th Amendment: Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Let’s Get Into It

Fast Facts About Bail

COVID-19 has exacerbated bail issues and led to longer stays in jail for people who have yet to have a trial. In New York, for example, for people who do not make bail, average jail stays have become longer. The average number of days people were in custody in New York City jails rose from 198.4 in January 2020, or roughly six and a half months, to 286.5 days, or more than nine months, in August 2021 – a 44% increase.

The average length of pretrial incarceration in the US is 26 days

At any given time an estimated half a million Americans, or about two-thirds of the overall jail population, are incarcerated because they can’t afford their bail or a bond.

About 94% of felony convictions at the state level and about 97% at the federal level are the result of plea bargains. That means only 3%-6% of all cases actually go to trial.

Why Does Bail Exist And How Does It Work?

From The Marshall Project:

You’ve been arrested, taken to jail, fingerprinted and processed. Within 24 to 48 hours, you’ll go to an initial hearing known as an arraignment.

There, a judge will formally present the charges against you, and you will plead innocent or guilty. Then the judge either grants bail and sets the amount; releases you on your own recognizance without a fee; or denies you bail.

Bail is usually denied if a defendant is deemed a flight risk or a danger to the community because of the nature of the alleged crime.

If you get bail, you have three choices:

Pay the amount in full and get out of jail. You’ll get the money back when the trial is over, no matter the outcome.

Pay nothing. You’ll return to jail and await trial.

Secure a bail bond and get out of jail. In this case, you’ll pay a private agent known as a bondsman a portion of the amount, usually 10 percent and collateral such as a home or jewelry to cover the balance. (In turn, bail bond companies guarantee the full amount to the court.) The fee you pay for a bail bond is not refundable, even if your charges are dropped.

Resources

Friends, the bail system is absolutely horrific, and this is just scratching the surface.

I plan on discussing bail a lot more in this newsletter since it’s something I’m focusing a lot of thought on in school. This newsletter is just the start so I wanted to cover the basics. My final paper for one of my classes will center around bail, specifically as it impacts New Yorkers. Bail is absolutely heinous and destroys people’s lives. Let’s keep talking about it. See ya next week!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

War On Drugs

The War on Drugs is a phrase used to refer to a government-led initiative that aims to stop illegal drug use, distribution and trade by dramatically increasing prison sentences for both drug dealers and users. This drug war has led to unintended consequences that have proliferated violence around the world and contributed to mass incarceration in the US.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 49 of this newsletter. This week’s topic is The War On Drugs. “The War on Drugs is a phrase used to refer to a government-led initiative that aims to stop illegal drug use, distribution and trade by dramatically increasing prison sentences for both drug dealers and users. The movement started in the 1970s and is still evolving today.” The War on Drugs was popularized by Richard Nixon who said, "If we cannot destroy the drug menace in America, then it will surely in time destroy us," Nixon told Congress in 1971. "I am not prepared to accept this alternative." This drug war has led to consequences that have proliferated violence around the world and contributed to mass incarceration in the US. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

The War On Drugs: The War on Drugs is a phrase used to refer to a government-led initiative that aims to stop illegal drug use, distribution and trade by dramatically increasing prison sentences for both drug dealers and users. The movement started in the 1970s and is still evolving today.

The Drug Scheduling System: Under the Controlled Substances Act, the federal government — which has largely relegated the regulation of drugs to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) — puts each drug into a classification, known as a schedule, based on its medical value and potential for abuse. You can view the current Drug Schedules here.

Let’s Get Into It

Drug Use In America Before The “War On Drugs”

According to historian Peter Knight, opium largely came over to America with Chinese immigrants on the West Coast. Americans, already skeptical of the drug, quickly latched on to xenophobic beliefs that opium somehow made Chinese immigrants dangerous.

Cocaine was similarly attached in fear to Black communities, neuroscientist Carl Hart wrote for the Nation. The belief was so widespread that the New York Times even felt comfortable writing headlines in 1914 that claimed "Negro cocaine 'fiends' are a new southern menace."

Drug use for medicinal and recreational purposes has been happening in the United States since the country’s inception. In the 1890s, the popular Sears and Roebuck catalogue included an offer for a syringe and small amount of cocaine for $1.50.

In some states, laws to ban or regulate drugs were passed in the 1800s, and the first congressional act to levy taxes on morphine and opium took place in 1890.

The Smoking Opium Exclusion Act in 1909 banned the possession, importation and use of opium for smoking.

In 1914, Congress passed the Harrison Act, which regulated and taxed the production, importation, and distribution of opiates and cocaine.

In 1919, the 18th Amendment was ratified, banning the manufacture, transportation or sale of intoxicating liquors, ushering in the Prohibition Era. The same year, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act (also known as the Volstead Act), which provided guidelines on how to federally enforce Prohibition.

In 1937, the “Marihuana Tax Act” was passed. This federal law placed a tax on the sale of cannabis, hemp, or marijuana. While the law didn’t criminalize the possession or use of marijuana, it included hefty penalties if taxes weren’t paid, including a fine of up to $2000 and five years in prison.

The War On Drugs

President Richard M. Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) into law in 1970.

In June 1971, Nixon officially declared a “War on Drugs,” stating that drug abuse was “public enemy number one.”

Nixon went on to create the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 1973.

In the mid-1970s, the War on Drugs took a slight hiatus. Between 1973 and 1977, eleven states decriminalized marijuana possession.

Jimmy Carter became president in 1977 after running on a political campaign to decriminalize marijuana.

In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan reinforced and expanded many of Nixon’s War on Drugs policies. In 1984, his wife Nancy Reagan launched the “Just Say No” campaign, which was intended to highlight the dangers of drug use.

In 1986, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which established mandatory minimum prison sentences for certain drug offenses.

On September 5, 1989, in his first televised national address as president, George H.W. Bush called drugs "the greatest domestic threat facing our nation today," held up a bag of seized crack cocaine, and vowed to escalate funding for the war on drugs. He later approved, among other drug-related policies, the 1033 program (then known as the 1208 program) that equipped local and state police with military-grade equipment for anti-drug operations.

It’s Impact On Incarceration And Racist History

The escalation of the criminal justice system's reach over the past few decades, ranging from more incarceration to seizures of private property and militarization, can be traced back to the war on drugs. After the US stepped up the drug war throughout the 1970s and '80s, harsher sentences for drug offenses played a role in turning the country into the world's leader in incarceration.

During a 1994 interview, President Nixon’s domestic policy chief, John Ehrlichman, provided inside information suggesting that the War on Drugs campaign had ulterior motives, he was quoted saying:

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.”

When the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act was passed, it was heavily criticized as having racist ramifications because it allocated longer prison sentences for offenses involving the same amount of crack cocaine (used more often by Black Americans) as powder cocaine (used more often by white Americans). 5 grams of crack triggered an automatic 5 year sentence, while it took 500 grams of powder cocaine to merit the same sentence.

Critics pointed to data showing that people of color were targeted and arrested on suspicion of drug use at higher rates than whites.

Overall, the policies led to a rapid rise in incarcerations for nonviolent drug offenses, from 50,000 in 1980 to 400,000 in 1997. In 2014, nearly half of the 186,000 people serving time in federal prisons in the United States had been incarcerated on drug-related charges, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

The number of Black men in prison (792,000) has already equaled the number of men enslaved in 1820. With the current momentum of the drug war fueling an ever expanding prison-industrial complex, if current trends continue, only 15 years remain before the United States incarcerates as many African-American men as were forced into chattel bondage at slavery's peak, in 1860.

The War On Drugs Today

Today, the US still continues to have the largest prison population on the planet. Learn more about it in my newsletters on Prison Reform.

Between 2009 and 2013, some 40 states took steps to soften their drug laws, lowering penalties and shortening mandatory minimum sentences, according to the Pew Research Center.

In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA), which reduced the discrepancy between crack and powder cocaine offenses from 100:1 to 18:1.

The recent legalization of marijuana in several states and the District of Columbia has also led to a more tolerant political view on recreational drug use. However, estimated 40,000 people today are incarcerated for marijuana offenses even as the overall legal cannabis industry is booming; one state after another is legalizing; and cannabis companies are making healthy profits.

Although Black communities aren't more likely to use or sell drugs, they are much more likely to be arrested and incarcerated for drug offenses.

A 2014 study from Peter Reuter at the University of Maryland and Harold Pollack at the University of Chicago found there's no good evidence that tougher punishments or harsher supply-elimination efforts do a better job of pushing down access to drugs and substance abuse than lighter penalties.

Most of the reduction in accessibility from the drug war appears to be a result of the simple fact that drugs are illegal, which by itself makes drugs more expensive and less accessible by eliminating avenues toward mass production and distribution.

Enforcing the war on drugs costs the US more than $51 billion each year, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. As of 2012, the US had spent $1 trillion on anti-drug efforts.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

The 13th Amendment

The 13th amendment to the Constitution made slavery illegal while repackaging it into a different form. The prison system in America turns those that are incarcerated into subhumans. Black men account for roughly 6.5% of the US population, but 40.2% of the prison population. Why is this? We can trace it back to the 13th amendment.

“So many aspects of the old Jim Crow are suddenly legal again once you’ve been branded a felon. And so it seems that in America we haven’t so much ended racial caste, but simply redesigned it.”

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 23 of this newsletter. Today’s topic is The 13th Amendment. I’ve spoken about the 13th amendment in my newsletters on The Prison Industrial Complex, Prison Reform: Week 1 and Prison Reform: Week 2. The 13th amendment to the Constitution made slavery illegal while repackaging it into a different form. The prison system in America is vile, exploitative and inhumane. I feel overwhelmed by fear to merely do a google image search of prison conditions in America, and yet, we disappear human beings into those conditions every single day. America has 5% of the world’s population but nearly 25% of its incarcerated population. (EJI) 1 in 17 white men are likely to go to prison in their lifetime, while 1 in 3 Black men receive imprisonment. Black men account for roughly 6.5% of the US population, but 40.2% of the prison population. Why is this? We can trace it back to the 13th amendment. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

The Abolition Amendment: A joint resolution introduced by Democrats that would remove the "punishment" clause from the amendment, which effectively allows members of prison populations to be used as cheap and free labor.

Prison Labor: Prison labor, or penal labor, is work that is performed by incarcerated and detained people. Not all prison labor is forced labor, but the setting involves unique modern slavery risks because of its inherent power imbalance and because those incarcerated have few avenues to challenge abuses. The minimum estimated annual value of incarcerated labor from U.S. prisons and jails is $2 billion, according to the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative. As recently as 2010, a federal court held that “prisoners have no enforceable right to be paid for their work under the Constitution.”

The Black Codes: Restrictive laws designed to limit the freedom of African Americans and ensure their availability as a cheap labor force after slavery was abolished during the Civil War. These were new laws that explicitly applied only to Black people immediately after the 13th amendment was passed and and subjected them to criminal prosecution for “offenses” such as loitering, breaking curfew, vagrancy, having weapons, and not carrying proof of employment. Crafted to ensnare Black people and return them to chains, these laws were effective; for the first time in U.S. history, many state penal systems held more Black prisoners than white.

The Prison Industrial Complex: A term we use to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems. This term is derived from the "military–industrial complex" of the 1950s and describes the attribution of the rapid expansion of the US inmate population to the political influence of private prison companies and businesses that supply goods and services to government prison agencies for profit.

Let’s Get Into It

“Neither Slavery Nor Involuntary Servitude, Except As A Punishment For Crime Whereof The Party Shall Have Been Duly Convicted, Shall Exist Within The United States, Or Any Place Subject To Their Jurisdiction.”

A Brief History

Chattel slavery existed in the United States from its founding in 1776 until the passing of the 13th amendment in 1865 (not really but, that’s the whole point of this blog post so just bare with me).

Our founding fathers—George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Patrick Henry were all slave-owners. 12 former presidents owned slaves, with 8 of them still owning human beings while in office.

By 1861, during the Civil War, more than 4 million people were enslaved in 15 southern and border states.

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect in 1863, announced that all enslaved people held in the states “then in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” The Emancipation Proclamation it itself did not end slavery in the United States, as it only applied to the 11 Confederate states then at war against the Union. To make emancipation permanent would take a constitutional amendment.

On January 31, 1865, the House of Representatives passed the proposed amendment with a vote of 119-56, just over the required two-thirds majority.

In late 1865, Mississippi and South Carolina enacted the first black codes. The Black Codes were restrictive laws designed to limit the freedom of African Americans and ensure their availability as a cheap labor force after slavery was abolished during the Civil War. Black codes varied from state to state. In South Carolina, one of these laws prohibited Black people from holding any occupation other than farmer or servant unless they paid an annual tax of $10 to $100. Mississippi’s law required Black people to have written evidence of employment for the coming year each January; if they left before the end of the contract, they would be forced to forfeit earlier wages and were subject to arrest. Black codes were also laws that made things like stealing something over $10 while being Black the equivalent of grand larceny. It made loitering or talking back to a white person grounds for imprisonment. In the years following Reconstruction, the South reestablished many of the provisions of the black codes in the form of the so-called "Jim Crow Laws."

The year after the amendment’s passage, Congress passed the nation’s first civil rights bill, the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 declared all male persons born in the United States to be citizens, "without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude." This tried to invalidate black codes, but many were repackaged into Jim Crow Laws.

After Reconstruction, for the first time in U.S. history, many state penal systems held more Black prisoners than white. Black codes made it very easy to imprison someone for an offense like not showing proper respect to a white person. States put prisoners to work through a practice called “convict-leasing,” where white planters and industrialists “leased” prisoners to work for them. Chain gangs of predominantly Black prisoners built many of today’s roads and farmed the land. Prisoners were not paid. Many Black prisoners found themselves living and working on plantations (that had been turned into prisons) against their will and for no pay decades after the Civil War.

Today, states and private companies still rely on prisoners performing free or extremely low-paid labor for them. For example, California saves up to $100 million a year, according to state corrections spokesman Bill Sessa, by recruiting incarcerated people as volunteer firefighters. The minimum estimated annual value of incarcerated labor from U.S. prisons and jails is $2 billion, according to the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative. As recently as 2010, a federal court held that “prisoners have no enforceable right to be paid for their work under the Constitution.”

Ratifying the 13th Amendment

The Abolition Amendment is joint resolution introduced by Democrats that would remove the "punishment" clause from the amendment, which effectively allows members of prison populations to be used as cheap and free labor.

States like Nebraska, Utah and Colorado have approved an amendment to remove language on the use of slavery as a punishment for convicted criminals. The passage of the measure will amend Section 21 of Article I of the Utah Constitution, removing language that disallowed slavery "except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." This makes prison labor voluntary.

Currently, OSCA’s (Occupational Safety Councils Of America) standards do not protect prison laborers, so if prisoners are forced to work in unsafe or dangerous situations, like working with toxic chemicals, they are not protected.

Learn more in this podcast: Closing the 13th Amendment Loophole, The Brian Lehrer Show WNYC

Resources

Sign This Petition From EJI - Sign this petition from the Equal Justice Initiative and call on Congress to amend the Thirteenth Amendment to make all slavery and involuntary servitude unconstitutional in the United States, without exception.

Watch 13th

13th is potentially the most impactful film I’ve ever watched on the topic of systemic racism. This comprehensive documentary explores the intersection of race, justice, and mass incarceration in the United States. DuVernay contends that slavery has been perpetuated since the end of the American Civil War through criminalizing behavior and enabling police to arrest poor freedmen and force them to work for the state under convict leasing; suppression of African Americans by disenfranchisement, lynchings, and Jim Crow; politicians declaring a war on drugs that weighs more heavily on minority communities and, by the late 20th century, mass incarceration affecting communities of color, especially American descendants of slavery, in the United States. Watch it for free on YouTube, or on netflix.

Next week, I’m going to be focusing on Black American Sign Language. I came across this topic recently and am so excited to learn more about BASL and how I can be an ally to those that use sign language. See ya there!

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Prison Reform: 2

Last week, we talked about the history of the prison system in The United States, this week, I want to focus more specifically on current prison conditions and the reform that folks are pushing for. We discuss bail. prison conditions, thee death penalty, excessive punishment for drug-related crimes, and re-entry back into society.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 17 of this newsletter! This is our second consecutive week focusing on the topic of Prison Reform. In case you missed the last newsletter, when we talk about prison reform, we are referring to the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, improve the effectiveness of the prison system, implement alternatives to incarceration and find ways to reinstate convicted individuals back into society after they serve their sentence.

Last week, we talked about the history of the prison system in The United States, this week, I want to focus more specifically on current prison conditions and the reform that folks are pushing for. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

“Three Strikes, You’re Out”: Starting with Washington in 1993, over half the states and the federal government enacted “three strikes” laws. The exact application of the three-strikes laws varies considerably from state to state, but the laws call for life sentences for at least 25 years on their third strike. In California, for example, it required that a person convicted of a felony who has two or more prior convictions for certain offenses must be sentenced to at least 25 years to life in state prison, even if the third offense is nonviolent. People have been sentenced to life in prison for shoplifting a pair of socks or stealing bread. More than two-thirds of people serving federal life or virtual life sentences today were convicted of nonviolent crimes, including 30% for a drug crime.

Recidivism: The re-arrest, reconviction, or re-incarceration of an ex-offender within a given time frame.

Let’s Get Into It

The Current Situation: Bail

The amount of bail depends on the severity of the crime but is also at the judge's discretion which means it is not standardized.

Bail amounts vary widely, with a nationwide median of around $10,000 for felonies (though much higher for serious charges) and less for misdemeanors (in some places such as New York City, typically under $2,000, though much higher in some jurisdictions). (Vox)

Bailed-out suspects commonly must comply with "conditions of release." If a suspect violates a condition, a judge may revoke bail and order the suspect re-arrested and returned to jail.

Sometimes people are released "on their own recognizance," or "O.R." A defendant released on O.R. must simply sign a promise to show up in court and is not required to post bail.

Historically, Black and brown defendants have been more likely to be jailed before trial than white defendants. (Prison Policy)

As of 2002 (the last time the government collected this data nationally), about 29% of people in local jails were unconvicted – that is, locked up while awaiting trial or another hearing. Approx 7 in 10 (69%) of these detainees were people of color. (Prison Policy)

Unconvicted defendants now make up about two-thirds (65%) of jail populations nationally. (Prison Policy)

As people await court hearings for months or even years, they suffer from inadequate medical care, dangerous conditions, and many lose their jobs and housing. (Vox)

They also have a higher chance of being convicted than if they hadn’t been assigned bail, as they take plea bargains just to get out of jail, whether or not they actually committed a crime. (Vox)

Reform: Bail

Current bail practices are unconstitutional in violating due process rights and equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment, the prohibition against excessive bail in the Eighth Amendment, and the right to a speedy trial guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment. (ACLU)

Organizations like the ACLU are specifically focused on ending in for-profit bail bond companies and the insurance companies who back them because the directly profit by providing bail, with high interest, for thee most vulnerable individuals who could not pay bail otherwise.

Most folks agree on one solution, end cash bail. Especially because bail is not even seen as an effective method for guaranteeing people return for trial. The Bail Project has an amazing reimagining for pretrial justice.

The Current Situation: Prison Conditions, The Death Penalty And Punishment

Doing this research was heartbreaking. I was genuinely covering my eyes afraid to see conditions of America’s prisons. I just want to stress that these are human beings being put in the most inhumane and frightening circumstances. A blurb in a newsletter honestly cannot do adequate justice to the dignity that these people deserve.

Private prisons house 8.2% (121,420) of the 1.5 million people in state and federal prisons. Private prison corporations reported revenues of nearly $4 billion in 2017. The private prison population is on the rise, despite growing evidence that private prisons are less safe, do not promote rehabilitation, and do not save taxpayers money. (EJI)

The fastest-growing incarcerated population is people detained by immigration officials. (EJI)

People who need medical care, help managing their disabilities, mental health and addiction treatment, and suicide prevention are denied care, ignored, punished, and placed in solitary confinement.

More than half of all Americans in prison or jail have a mental illness.

Incarcerated people are beaten, stabbed, raped, and killed in facilities run by corrupt officials who abuse their power with impunity. These are some examples taken from the Equal Justice Initiative:

Prisoners being handcuffed, stripped naked, and then beaten by guards (EJI)

Correctional officers forcing young incarcerated men to perform sex acts and threatening to file disciplinary charges against them if they refused or reported the abuse (EJI)

Correctional officers caught engaging in physical or sexual misconduct are often being transferred to other facilities, not fired (EJI)

Drugs and other contraband are often brought into the prisons and sold to prisoners by officers or staff (EJI)

Cuts are constantly been made to mental health and drug treatment services and rehabilitative programming, and recreation including the removal of books and other resources (EJI)

Sexual abuse including female inmates being raped and impregnated by male correctional officers and female inmates viewed showering and using the bathroom is frighteningly common and often unreported out of fear (EJI)

Excessive punishments, especially for drug-related offenses

Wrongful convictions are also an issue with the current prison system. Read more about them here.

Despite growing bipartisan support for criminal justice reform, the private prison industry continues to block meaningful proposals.

The Death Penalty

Black Americans make up 42% of people on death row and 34% of those executed, but only 13% of the population in America is Black. (EJI)

The death penalty in America is a “direct descendant of lynching.” Racial terror lynchings gave way to executions.

By 1915, court-ordered executions outpaced lynchings for the first time. Two-thirds of people executed in the 1930s were Black, and the trend continued.

For every 9 people executed, there is 1 person found innocent on death row. (EJI)

Children were executed in the U.S. until 2005, and only in the last decade has the Supreme Court limited death-in-prison sentences for children. Kids as young as 8 can still be charged as an adult, held in an adult jail, and sentenced to extreme sentences in an adult prison.

Excessive Punishment For Drug-Related Crimes

According to the ACLU’s original analysis, marijuana arrests now account for over half of all drug arrests in the United States. Of the 8.2 million marijuana arrests between 2001 and 2010, 88% were for simply having marijuana.

An estimated 40,000 people today are incarcerated for marijuana offenses even as: the overall legal cannabis industry is booming; one state after another is legalizing; and cannabis companies are making healthy profits. (Forbes)

Reform: Prison Conditions

The Centre for Justice and Reconciliation believes restorative justice can be achieved with these improvements:

Reduce Idleness: Reduce idleness and increase recreational activity in prisons

Classify Prisoners: Classify prisoners by their level of risk, lower risk groups require less security

Improve Sanitation: Improve sanitation and healthcare

Grow Food: Grow food and raise livestock to both improve nutrition and provide a skillful activity

Use Volunteers: Have volunteers create programming

Train Staff: Train staff beyond disciplinary measures

Review Cases: Reduce the number of non-sentenced prisoners by establishing a process for lawyers, prosecutors and judges to review the legal status of individual detainees

Speed Release: Speedily release those awaiting trail by organizing volunteer lawyers or paralegal volunteers to help inmates prepare for bail hearings

Increase Alternatives: Use alternative community-based punishments rather than prison for non-dangerous offenders

Use Furloughs: Permit trustworthy prisoners to leave during the day or weekends for employment, family visitation or community service activities

Other recommendations for reform include increasing transparency to the public, treating the mentally ill in other facilities and ways rather than imprisoning them with little to no resources, making sure prisons are completely drug free to allow for rehabilitation, having a 0 tolerance policy with abusive correctional officers, creating a better schooling and vocational program, ending solitary confinement, rehabilitating communities of color where there are vulnerable ex-convicts.

The Current Situation: Re-Entry Back Into Society

Within three years of release, 67.8% of ex-offenders are rearrested, and within five years, 76.6% are rearrested. (Simmons University)

After you are legally a convicted felon, rights that you lose include: voting rights, right to bear arms, the ability to work in certain jobs and the difficulty of having to disclose your record on all job applications, the ability to receive student loans or financial aid, serving on a jury, traveling outside of the country (you can obtain a passport but travel restrictions may deny a convict admission), parental rights.

According to the Bureau of Justice, only 12.5% of employers said they would accept an application from an ex-convict. (Simmons University)

Phone calls and written communication to and from prisons are very expensive because of surcharges from companies and/or the prisons themselves. Because of this, inmates are often estranged from their family and have a harder time bonding and connecting after release.(Simmons University)

Advances in technology, living will less regimented structure, unrealistic expectations, shifts in the home dynamics, and other large changes make it difficult to reintegrate and the prison system does not privide adequate support.

82% of prisoners expected that their parole officers would help in their transition home, after release only about half reported that their parole officers were helpful during their transitions. (Simmons University)

Many ex-offenders are not given a new driver’s license simply because of their criminal record, but yet must drive to work, or drive to see their parole officers. They receive fines for driving without a license, which contributes to their debt and complicates their access to a license. (Simmons University)

Reform: Re-Entry Back Into Society

Many of the challenges facing ex-offenders are systemic and require policy changes and a shift away from the attitude that punishment should continue after sentences have been served.

People need support from the prison system and federal government when being released — from finding a job (without being discriminated against) to finding safe housing and becoming self sufficient.

“Ban the Box” is a national campaign against continued punishment in hiring that calls for employers to remove the box on job applications that requires applicants to disclose criminal records.

Programs like The Prison University Project help inmates earn college degrees while incarcerated. A 2013 National Criminal Justice Reference Service study found that when inmates complete degrees before re-entering society, recidivism rates substantially decrease.

The “Ride Home Program External” in California employs ex-offenders to pick up inmates on the day of their release so they can get them home, but also help facilitate their transition to life on the outside.

This start-up, Pigeonly, makes it less expensive to stay in contact with inmates.

Ultimately, the prison system in America is cruel. It strips humans of their rights and dignity and once they serve their time, these people are told they are still not able to be reinstated as full members of society. From bail, to the violent prison system, and ultimately through re-entry, these individuals, especially Black and brown people, are treated subhuman.

ACTION STEPS

It takes a few minutes to sign these petitions, don’t hesitate, make the time now.

RESOURCES

Prosecutors Need To Take The Lead In Reforming Prisons From "The Atlantic"

After Cash Bail: A Framework For Reimagining Pretrial Justice

SUPPORT

I’ve personally donate almost $1,000 to The Bail Project in the last 6 months through fundraising classes, donation matching, and my own personal contributions. As you read above, the cash bail system is horrific. It’s responsible for the deaths of Sandra Bland, who could not pay her $515 bail and died in jail, and Kalief Browder, a 16 year old child who was stopped by police and accused of robbery, and ended up spending three years on Rikers Island as he awaited trial, because he could not afford bail. He was brutalized and suffered injuries both physically and emotionally, eventually committing suicide at home after the prosecutor dropped all charges and released him. Donate today.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Prison Reform: 1

Prison reform is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, improve the effectiveness of the prison system, implement alternatives to incarceration and find ways to reinstate convicted individuals back into society after they serve their sentence. This topic will be broken down into 2 weeks, this week we get some background and history on the prison system in America, next week we talk more about conditions and key reform points.

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 16 of this newsletter! This week’s topic is Prison Reform. Prison reform is the attempt to improve conditions inside prisons, improve the effectiveness of the prison system, implement alternatives to incarceration and find ways to reinstate convicted individuals back into society after they serve their sentence.

I’ve talked about the Prison Industrial Complex before, but because there is so much to unpack here, this will be a 2-week long topic. This week I will share more resources on the history of our current prison system in America and the ways in which scholars, activists and prisoners have linked the exception clause in the 13th Amendment to the rise of a prison system that incarcerates Black people at more than five times the rate of white people, and profits off of their unpaid or underpaid labor. Next week, I will talk about prison conditions and the specific areas of reform we are fighting for.

On a personal note, reform is a key cause for me and something I have and will continue to advocate for for the rest of my life. Angela Davis said, “Prisons do not disappear social problems, they disappear human beings,” and the ways in which human beings are so reduced, mistreated, tortured and killed in our prisons cannot be accepted. Let’s get into it.

Key Terms

Prison: An institution (such as one under state jurisdiction) for confinement of persons convicted of serious crimes. So if you’re sentenced and serving your time, it’s probably in a prison.

Jail: Such a place under the jurisdiction of a local government (such as a county) for the confinement of persons awaiting trial or those convicted of minor crimes. So if you’ve committed a minor offense and are awaiting trial, it’s probably in a jail.

Bail: Bail works by releasing a defendant in exchange for money that the court holds until all proceedings and trials surrounding the accused person are complete. That means if a defendant goes to all of their proceedings and trials, they get their money back. The amount of bail depends on the severity of the crime but is also at the judge's discretion which means it is not standardized. If you cannot pay bail, you must stay in jail until trial.

Surety Bond: When a defendant cannot afford bond, they can contact a bail agent or bail bondsman. A bail agent is backed by a special type of insurance company called a surety company and pledges to pay the full value of the bond if the accused doesn't appear in court. In return, the bail agent charges his client a 10 percent premium and collects some sort of collateral like a house or car.

Corporal Punishment: Physical punishment.

War on Drugs: The War on Drugs is a phrase used to refer to a government-led initiative that aims to stop illegal drug use, distribution and trade by dramatically increasing prison sentences for both drug dealers and users. The movement started in the 1970s and is still evolving today. Richard Nixon started the “War on Drugs” and his domestic policy chief was quotes saying: “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.”

The Black Codes: Restrictive laws designed to limit the freedom of African Americans and ensure their availability as a cheap labor force after slavery was abolished during the Civil War.

Chain Gangs: Chain gangs were groups of convicts forced to labor at tasks such as road construction, ditch digging, or farming while chained together. Some chain gangs toiled at work sites near the prison, while others were housed in transportable jails such as railroad cars or trucks. Chain gangs minimized the cost of guarding prisoners, but exposed prisoners to painful ulcers and dangerous infections from the heavy shackles around their ankles.

Let’s Get Into It

A Brief History Of Prisons In America

Scroll down for more details on the prison system in relation to slavery and its impact on Black Americans specifically.

In colonial America, fining and corporal punishment were used as repercussions to crimes. This included whippings and hangings.

In the 1800s prisons were more common over physical punishments or the death penalty, but prisoners shared common spaces and had access to goods like alcohol.

In 1820, New York implemented the Auburn system named after Auburn State Prison where it was utilized. This was a system in which prisoners were confined in separate cells and prohibited from talking when eating and working together. They worked together in groups during the day and were in solitary confinement at night. The goal was supposedly rehabilitation and reflection. This system was widely adopted.

In the 1860s, prisons were overcrowded and it was clear that reform and rehabilitation were not the focus. Enoch Wines and Theodore Dwight implemented an education program focused on vocational training to remedy this problem.

In the early 1900s, psychiatrists started to treat prisoners but most methods were the same including restraining and solitary confinement. Probation was introduced at this time.

The 1950s brought a series of riots and an outcry for prison reform. Since the 1960s the prison population in the US has risen steadily, even during periods where the crime rate has fallen.

The 1970s “War on Drugs” resulted in more densely packed prisons.

By 2010, the United States had more prisoners than any other country and a greater percentage of its population was in prison than in any other country in the world. (Prison Policy Initiative)

Today, 6 out of 10 people in U.S. jails—nearly a half million individuals on any given day—are awaiting trial. People who have not been found guilty of the charges against them account for 95% of all jail population growth between 2000-2014. (PJI)

The 13th Amendment And The Exploitation Of Black Americans

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

The 13th Amendment abolished slavery (but not really) in 1865. That same year, The Black Codes were passed and things like not showing respect, “malicious mischief” or loitering were offenses that landed newly freed slaves in prison. (History)

Many plantations in the south converted into prisons and stayed that way for over 100 years. The Corrections Corporation of America, a $1.8 billion private prison corporation, was founded by Terrell Don Hutto, who ran a cotton plantation the size of Manhattan in Texas until 1971. For-profit private prisons are concerned only with profit, not with rehabilitation. One prisoner wrote in his memoir that, as soon as the prison was privatized, his jailers “laid aside all objects of reformation and re-instated the most cruel tyranny, to eke out the dollar and cents of human misery.”(Time)

States put prisoners to work through a practice called “convict-leasing,” whereby white planters and industrialists “leased” prisoners to work for them. States and private businesses made money doing this, but prisoners didn’t. Convict leasing ended in 1910, however, companies like Whole Foods, Starbucks and Victoria Secret have benefited from prison labor in the past. (PBS)

Today — we see modern convict-leasing in cases such as California using incarcerated people as firefighters, saving the state $100 Million per year with their unpaid labor. The inmates earn $2 a day while in the camps and $1 an hour when out battling fires. (KQED)

Statistics

The U.S. has 5% of the world’s population but nearly 25% of its incarcerated population. (EJI)

32% of the US population is represented by Black and Hispanic people, compared to 56% of the US incarcerated population being represented by Black and Hispanic people. (NAACP)

A Black man is more than 5 times more likely to go to prison is his life than a white man. (US Department of Justice)

Compared to white men charged with the same crime and with the same criminal histories, Black men receive bail amounts 35% higher; for Hispanic men, bail is 19% higher than white men. (PJI)

People who cannot afford bond receive harsher case outcomes. They are 3 - 4 times more likely to receive a sentence to jail or prison, and their sentences are 2 - 3 times longer.(PJI)

Support

Support the Equal Justice Initiative. EJI strives to end mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States. They fight for those who have been wrongfully convicted, especially Black Americans. They are champions of prison reform from fighting against the death penalty to fighting for children in adult prisons to improving prison conditions.

Support The Bail Project. The Bail project combats mass incarceration through their national revolving bail fund. Remember that statistic earlier about 6 out of 10 people in U.S. jails—nearly a half million individuals on any given day—are awaiting trial? Those individuals, who are innocent until proven guilty, should be awaiting trial at home, and would be if they could pay for bail.

Next week, I’ll be talking more about Prison Reform, specifically current prison conditions and the ways in which amazing organizations like EJI and The Bail Project, amongst others, are fighting for reform in various areas, as well as ways you can fight too. I’ll see you there.

“We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, we are the change we seek” — With love and light, Taylor Rae

Prison Industrial Complex

The Prison Industrial Complex is a term we use to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems. The US makes up about 5% of the world’s population but 25% of it’s prison population. Why? The answer is profit.

“Prisons do not disappear problems, they disappear human beings.”

Hi Friends!

Welcome to Issue 7 of this newsletter! This week’s topic is The Prison Industrial Complex. The prison industrial complex (PIC) is a term we use to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems. This term is derived from the "military–industrial complex" of the 1950s and describes the attribution of the rapid expansion of the US inmate population to the political influence of private prison companies and businesses that supply goods and services to government prison agencies for profit. Let’s get into it!

Key Terms

Prison Industrial Complex: Describes the attribution of the rapid expansion of the US inmate population to the political influence of private prison companies and businesses that supply goods and services to government prison agencies for profit. The term also refers to the network of participants who prioritize personal financial gain over rehabilitating those that have been imprisoned.

The 13th Amendment: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Scholars, activists and prisoners have linked that exception clause to the rise of a prison system that incarcerates Black people at more than five times the rate of white people, and profits off of their unpaid or underpaid labor.

Let’s Get Into It

Though only 5 percent of the world’s population lives in the United States, it is responsible for approximately 25 percent of the world’s prison population. (Washington Post) The Prison Industrial Complex helps maintain the authority of people who get their power through racial, economic and other privileges. There are many ways this power is collected and maintained through the PIC, including creating mass media images that perpetuate stereotypes of marginalized communities as criminal, delinquent, or deviant.

The most common agents of the Prison Industrial Complex are corporations that contract cheap prison labor, construction companies, surveillance technology vendors, companies that operate prison food services and medical facilities, correctional officers unions, private probation companies, lawyers, and lobby groups that represent them.

The portrayal of prison-building/expansion as a means of creating employment opportunities and the utilization of inmate labor are particularly harmful elements of the Prison Industrial Complex as they boast clear economic benefits at the expense of incarcerated human beings.

Do You Know What Happens To Your Rights When You Get Convicted?

Essentially, your citizenship is revoked. You serve your time and upon release, you are left with very little. In America, the systems in place don’t allow you to pay your debt to society and rehabilitate your life, they insist that you are punished for the rest of your life.

Right to Bear Arms

Right to Vote

Jury Service

Right to Travel Abroad

Parental Rights

Public Assistance and Housing

Employee Discrimination

“The term “prison industrial complex” was introduced by activists and scholars to contest prevailing beliefs that increased levels of crime were the root cause

of mounting prison populations. Instead, they argued, prison construction and the attendant drive to fill these new structures with human bodies have been driven by ideologies of racism and the pursuit of profit. ”